Thoughts on Place

“Place,” as described by Tim Cresswell in his enlightening book Place: An Introduction, is a concept that is powerful in both simplicity and complexity. Cresswell explains how it is “not a specialized piece of academic terminology” but a “word we use daily in the English-speaking world.” Its usage has led to the assumption that it is a simple term used by all with common sense, but complexities have allowed “place” to have a diversity of uses. Before considering how I plan to use place in my research, this anthology examines the complicated nature of “place” that has allowed a vast array of usages.

Walter Mignolo is explicit when discussing the decolonial power of place through his concept of “decolonial localism.” Mignolo applies decoloniality to place because colonialism is the removal of place. It attempts to force indigenous people to behave as if they see their locality in the same manner as the colonizers: a “blank space” to be exploited. Colonialism has impacted people’s sense of place globally in this way, as is visible through Western hegemony and the resultant rise of “placelessness.”

Without place, we are disorientated and disconnected from our ancestors who occupied the same place as us. “Place” is, therefore, most potent where it serves as a “place of memory,” ensuring that the experience of our ancestors is never forgotten.

Maintaining place is most pressing where these “places of memory” remind us of our recent history. In Sierra Leone, the “Truth and Reconciliation Commission” created the “Sierra Leone Peace Museum” in 2013. It works to preserve documentation and present a narrative history of the Civil War for visitors. Such museums are examples of “places of memory.” Ensuring that experiences of conflict and violence are remembered and thus propagating future peace.

Places like the Sierra Leone Peace Museum are performative, and the location selected for the exercise of “place” is intentional. Visitors can find the museum at the site of the Special Court

for Sierra Leone, an international tribunal that tried those accused of war crimes in the civil war. The court became the first to convict warlords for their use of child soldiers, and the severity of these crimes makes it a compelling selection of place for the Sierra Leone Peace Museum. It has added permanence to this place, meaning its function of holding warmongers in Sierra Leone is continued by highlighting the horrors they created during the war.

My place-based approach to natural resources will also be performative as it is functional. Disentangling artisanal miners from exploitative international supply chains will allow them to earn the full value of the diamonds they extract. No longer forced to maximize extraction, they will be free to steward their land, receiving from it only the diamonds they require to be empowered. Therefore, the performance of mining in their indigenous place will shift to become less harmful to the local ecology and the health of indigenous people. Having made this change, the mine will become a performative node for removing neocolonial control, displaying an alternative path to uncontrolled extractivism.

References

- Cresswell, Tim (2015) Place: An Introduction, Chichester: Wiley.

- Mignolo, Walter (2011) The Darker SIde of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options, Durham, North Carolina, Duke University Press.

- Residual Special Court for Sierra Leone, viewed 12/01/2021, http://www.rscsl.org/.

- Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Peace Museum, viewed 12/01/2021 https://www.sierraleonetrc.org/index.php/sierra-leone-peace-museum.

Thoughts on Place-Based Knowledge

Ecosystems are chaotic, unpredictable, and uncontrollable. People must exist within them, not alter ecosystems to fit their purposes. Doing so is dangerous because of the “deterministic chaos” that rules an ecosystem’s operations. The “butterfly effect” illustrates this: “Tiny disturbances can produce exponentially divergent behavior.” This anthology explores how indigenous knowledge can be leveraged so that people can exist within these complex ecosystems.

Many frameworks have been proposed that offer the chance for a more sustainable society, including “waste equals food.” This is the concept that all capturable waste products must have a productive use in another space. However, even this solution will not create perfectly sustainable ecosystems, as some waste products such as carbon dioxide will inevitably escape. These greenhouse gases have the potential to destabilize the fragile “Gaia self-regulation,” and therefore, Fritjof Capra proposes that genuinely sustainable systems must “use only as much energy as it can capture from the sun.”

While Capra is correct in diagnosing the problem, he is mistaken in prescribing a solution. He argues that sustainable societies “modeled after nature’s ecosystems” will be “sustainable, not efficient.” The implication is that a downgrade in the utility of technology is necessary to upgrade sustainability. Harnessing place-based indigenous knowledge through Julia Watson’s “Lo Tek” proposes a means to create complex and efficient designs that do not sacrifice sustainability.

Watson proposes that the current innovation paradigm is “drowning in knowledge while starving for wisdom.” Instead, she suggests the “radical indigeneity” that has created hundreds of innovations for every ecosystem on earth inspires current design. These innovations have existed in symbiosis with the natural environment for thousands of years, using local resources to fulfill place-based needs, and following the rules of “guardianship” to ensure that their designs always hold a reciprocal relationship with their non-human surroundings.

Indigenous solutions have inherent eco-literacy because they are place-based, and they hold specific knowledge that is only accessible to those situated in their place. Whereas modern design often creates solutions for communities they have no intimate connections to, indigenous communities rely on the health of their surrounding ecosystem to survive. If their local ecology collapses, the survival of an indigenous group is heavily jeopardized, so their designs must be fitting with their local context.

Watson refers to this as “Lo Tek” to refer to how these indigenous solutions are often mistaken for showing a lack of development. I am familiar with this from when I returned to Kono District, Sierra Leone. Influenced by Western ontologies of progression, I drove past villages that had not changed since my exile and automatically thought of them as “backward.” Realizing I had picked up this ontology and the epistemologies that underlie them has forced me to question how I can envision a better solution for a place I am not living in. What right do I have to displace the indigenous systems in Kono for decades?

Moreover, as I continue to research in Kono, I will acquire valuable indigenous knowledge. When I am applying this indigenous knowledge alongside transition design to create place-based designs in the natural resources space, I must make sure I have learned from it without falling into the trap of appropriation.

References

- Capra, Fritjof (2005) “Speaking Nature’s Language: Principles for Sustainability” in Ecological Literature: Educating Our Children for a More Sustainable World, ed. By Michael K. Stone and Zenobia Barlow, San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, pp. 252-257.

- Goodwin, Brian, (1998), “The Edge of Chaos” in The Spirit of Science: From Experiment to Experience, ed. by David Lorimer, Edinburgh: Floris, pp. 149-161.

- Sheldrake, Rupert (1994) The Gaia Hypothesis, in The Rebirth of Nature: The Greening of Science and God, Rochester: Park Street Press, pp. 153-157.

- Watson, Julia (2019) Lo Tek: Design by Radical Indigenism, Cologne: Taschen.

- Whitt, Roberts, Norman and Grieves (2001) “Indigenous Perspectives”, in A Companion to Environmental Philosophy, ed. by Dale Jamieson, Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 42-53

“Small” is More complex than “Big”

I first heard this idea at a conference where Jonathan Chapman spoke about his book- “Design that Last.” He mentioned that sometimes we are sold on the idea that big/large is complex and small is simple.

Pulling on this thread further, I realized that organizing and maintaining small systems requires complex threading of principles. Creating small contextualized and localized specificity can quickly become more complex than large mono systems. Before I heard this idea, I assumed that small is simple, and large tends to be more complicated. Scale reduces complexity by universalizing truths as homogeneous. Before this encounter, I was sold to the idea that we require simplicity to be efficient.

Much of my background entrepreneurship is currently led by a ‘bigger is better’ concept, that big things are complicated, modern, and developed, and small things are simple and even backward. There is an obsession with making something universal that will change the lives of everyone on earth. Terry Irwin refers to these as “preplanned and resolved solutions” that are imposed without thought upon a context. They restrict the capabilities of indigenous people to design for their context.

Optimizing scale requires reductionism because universal ideas conflict with the localized specificity of an area. This conflict is displayed in Toluwalogo Odumosu’s study “Making Mobiles African,” which observes how Western designed mobile phones have been applied to the African context without considering how they would need to operate differently for African localities. Indigenous people have had to create new patterns of usage through “constituted appropriation” to make their devices functional, but the non-indigenous telecommunication companies did not predict the increased network demands from these usage patterns. It was not until indigenous telecommunications workers operated the network that the indigenous usage patterns were manageable.

Odumosu’s case study of mobile phones illustrates the perils of universalizing reductionism. When scale is optimized, a singular design is imported and universally applied to expect the context to adapt to it.

Fractal ontology is the process of learning from our surroundings, drawing from “experience and observation as opposed to theoretical abstraction”. They exist as a polar opposite to this reductionism, arguing that while contextualization is complex, it is necessary to ensure that design fits the localized specificity of the people. Scholars of fractal epistemologies allow local people to leverage their “selfhood” to design for a unique context. This “selfhood” must exist within dynamic and interrelated stable systems in a manner that is self-organizing and regenerative.

I have also had to tackle this problem in my work, which has moved in line with fractal epistemologies during my academic career. Initially, I hoped to design a holistic solution for the entire problem space of Distributed Natural Resource Systems, but a more fractal positionality has shifted my position. Now, I hope to generate small, meaningful impacts that are specific to the Kono District, Sierra Leone context.

References

- Bourget, Chelsea (2020) LIVING TREES AND NETWORKS: AN EXPLORATION OF FRACTAL ONTOLOGY AND DIGITAL ARCHIVING OF INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE, University of Guelph.

- Irwin, Terry (2015) “Transition design: A proposal for a new area of design practice, study, and research”, Design and Culture, 7(2), pp. 229-246.

- Jaques, William S. (2013) Fractal Ontology and Anarchic Selfhood: Multiplicitious Becomings, McMaster University.

- Odumosu, Toluwalogo (2017) “Making Mobiles African”, in What do Science, Technology, and Innovation Mean from Africa?, ed. by Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

On Cooperating with the Natural Environment

Behaving in harmony with our ecosystems requires us to apply Theodore Roszak’s “ecopsychology,”; the idea that we must live in balance with nature for our physical, emotional, and spiritual wellbeing. Following “ecopsychology” forces me to ask as I think about my entrepreneurship practice with a place-based lens, “what is here?”, “what will nature permit here?” and “what will nature help us do here?” whenever we are designing for a locality.

Ecopsychology is born from the desire to obtain a “Gaia” connection with local ecosystems, acknowledge that our earth is fragile “homeostasis,” and avoid destabilizing its fragile networks.

Maintaining an “ecopsychology” led approach is further complicated when applying it to natural resources, as extraction is the process of removing something from within the system. All current extraction has an ecological impact, causing damage to the extracted land, polluting the air, and poisoning waterways. My designs within this space must do better, “receiving” not “taking” from the land, by mitigating environmental impacts and sustaining extraction only as long as it is required to empower indigenous people in the locality. If resources cannot be “received” from an ecosystem without exploiting it, we must challenge if extraction can occur within that system.

Making interventions into a locality’s ecosystem requires an intimate knowledge of the complexities within that ecosystem to recognize its complexity and position within the wholeness of the planet. Therefore a “Gaia” connection, acting in synchrony with the local ecology, can only occur by having experience of that place. It is mistaken for outsiders to enter a locality’s ecosystem and expect to make more ecoliterate interventions than the indigenous people.

Overcoming these difficulties is only possible through research while embedded within my locality of interest: Kono, Sierra Leone. My previous study made the error of only considering human actors, driven by solutions that could empower them without considering the impact of my efforts on the natural environment. Last year’s research trip comprised two months focusing

on the inequities in the diamond supply chain from the Kono perspective, but it missed the ecological destruction of land from mining that was happening before my eyes.

My future research must transfer a significant proportion of my energy to environmental factors, leveraging indigenous knowledge to understand how the Kono people have existed in synchrony with their ecology for centuries. Cultural probes and narrative inquiry techniques will allow me to gauge how the Kono people position themselves within their ecosystems.

References

Lovelock, James E. and Margulis, Lynn (1974) “Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the gaia hypothesis”, Tellus, 26:1-2, pp. 2-10.

Roszak, T., Gomes, M. E., & Kanner, A. D. (1995). Ecopsychology: Restoring the earth, healing the mind. Sierra Club Books.

Geo-Futurism: Imagining New Realities for a Post-Extractive Africa

Close your eyes,

Imagine the diamonds that are still in the crust of the earth,

Imagine the indigenous people who live peacefully above these diamonds,

Imagine the mining conglomerate executive signing to acquire the land,

Imagine the bulldozers rolling up to force the indigenous farmers of their land,

Imagine the tones of heavy machinery rumbling onto the land and digging up layers of earth that have not been seen for thousands of years,

Imagine the ground shaking and the boom of destruction that fills the air,

Imagine the pollution that fills the flows into the waterways and is drunk by the indigenous people,

Imagine the indigenous locals, forced to remain in their polluted locality by international borders,

Imagine the first diamond found on the land and the miner who pockets just $5 for his discovery.

Now imagine the world is different,

Imagine an absence of top-down and coercive control of land by outsiders,

Imagine the indigenous landholder has a stewardship and the freedom to work their land how they want,

Imagine they leverage indigenous knowledge to understand their relationality and participation in the “more than human world.”

Imagine they utilize resources in harmony with the local ecosystem,

Imagine a stable dynamic, interrelated system that is self-organizing and regenerative.

To imagine this future is to imagine a world in which indigenous people would gain sovereignty over their land. Fresh water and resources would no longer be controlled by the government or wealthy corporations, and indigenous people could achieve sustenance from the resources available in their locality. Without relying on the Western hegemony for survival, indigenous people’s behavior will no longer be altered from having to placate this hegemon. They will be

able to reframe resources from something to be “taken” for financial gain to something to be “received” for sustenance.

Africa as a country will be eco-focus and empowered. The countries, territories, regions, lands, the biosphere, and humans could exist in harmony, “receiving” the necessities of life from each other and cohabiting the same localities peacefully. Through a Geo-Futurist lens, Africa looks beyond aid and extraction as a continent with empowering rich ecosystems and indigenous knowledge.

References

- Acland, Olivia (2017) “One Man’s Search for Diamonds”, BBC News, last seen 12/02/2021, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/in-pictures-38302289.

- Escobar, Arturo (2015) “Degrowth, postdevelopment, and transitions: a preliminary conversation”, Sustainability Science, 10(3), p. 456

- Linne, Diane l. et al (2017) “Overview of NASA Technology Development for In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU)”, 68th International Astronautical Congress, p. 1.

Thoughts on Place-base Natural Resources and Disability

The cotton tree is famous in Sierra Leone not for its trunk as wide as a car or its sprawling canopy but for the scores of beggars who work under it. They are usually disabled, affected by blindness or the loss of limbs from the civil war. These beggars often have their children with them who are deprived of normal education as their entire days are spent begging on the streets. One in three Africans lives below the global poverty line, including vast amounts of non-disabled people, systematically prevented from gathering the necessities for life. When access to these necessities is already challenging, how hard must it be for people struggling with disabilities? And what is our obligation to help?

I continue to wrestle with these questions as an entrepreneur and designer who prototypes ideas and implements them in Africa. I also think about what role economic empowerment in natural resources for Sierra Leone plays in tackling this big systemic problem in not just Sierra Leone but also other African countries.

The rights to these resources are for all citizens of that place. All too often, the disabled do not gain from the economic benefits of these natural resources as government institutions have failed to cater to their needs. So what small and impactful steps can be put in place to include them as citizens with a right to their place-based resources? How might I create inclusive, sustainable models in the natural resource space for the diable? How might I think beyond providing aid as a means of survival to provide job opportunities for personal empowerment for the disabled?

In the north, progress is clear in bringing disabled people back into the community as actors with value. Charities like EPIC (Empowering People for Inclusive Communities) help young disabled people become leaders in their communities and take on previously barred roles. Disabled teenagers working with EPIC are given leadership education and opportunities to help develop their local communities. Through this valuable education and the multitude of skills gained, the teenagers will access new pathways into employment, higher education, and healthier lifestyles.

Charities like EPIC are effective because they create flexible spaces that accommodate different bodies’ functions. These spaces become those of self-development and skill acquisition, preparing young people for the adult world and allowing them to find their value within it. It transforms the outside world from friction and difficulty to opportunity.

Organizations like EPIC are important in reframing how we view disability. Sarah Hendren discusses this reframing at a great length, responding to a study by the WHO, which found that roughly 1 billion people are disabled in the world. In her book What Can A Body Do? Hendren argues that disability has less to do with the minds and bodies of the disabled than it has to do with how the able world responds to it. She argues that disability arises when the “shape of the world…operates rigidly, with a brittle and scripted sense of what a body does or does not do.”

Rigidity isolates and “others” who cannot fit with the able-bodied world. It forces them to become “misfits” to borrow Rosemarie Garland-Thomson’s ingenious description. “Misfits” clarifies that it is the intersection between the body and the designed world where disability is produced. “Misfits” also empowers disabled people to highlight where society has gone wrong and to use their wisdom to light a new path.

Hendren’s work and charities like EPIC are insightful because they do not seek to change the bodies of disabled people but to make the world more flexible for disabled bodies. In “What Can A Body Do?” Hendren makes this most apparent when introducing us to those who have lost body parts, such as Audre Lorde: the poet, writer, and activist. Lorde opted out of a mastectomy, telling the world that bodies are not binary: disabled or abled. They exist in plurality, and people learn to use their bodies most effectively when society allows them to function without costly prosthetics.

The precedent set by organizations like EPIC is fascinating, and this framework must be tested and implemented in new spaces. As I take the Root Diamond initiative to Sierra Leone, integrating the disabled is a priority. This could be through using the profits to create spaces for the education of the disabled to follow the model of EPIC or by creating spaces for their gainful employment. Diamond cutting, for example, is a highly-skilled job that requires the worker to sit

for an extended period. This could be excellent to get those who cannot walk involved in Root Diamond.

In recent history, natural resource economies have been a place of excessive greed and exploitation. It is not only the planet ravaged but also the people living in natural resource-rich areas. The prosperity that their homes should have provided has been stolen from them. Designers in this space have an opportunity to transform the industry into something more humane.

Positionality: Negotiating my Own Complexities

“It turned out that the question of who I was, was not solved because I had removed myself from the social forces which menaced me—anyway, these forces had become interior, and I had dragged them across the ocean with me. The question of who I was had at last become a personal question, and the answer was to be found in me.”

James Baldwin, “Introduction,” in Nobody Knows My Name, 1961.

I am a privileged American citizen-immigrant originally from Sierra Leone but embedded within an elite university institution. My positionality has led me to constantly negotiate between my epistemologies and ontologies originating from the global north and south. As is the case for many in immigrant communities, I have significant anthropological, intellectual, and professional contradictions that have had an unconscious impact on my work. I am ethnically Sierra Leonean, but I have studied in the USA, where a Western education has given my subjective mind Western epistemologies.

At times, I have fallen for the narrative of modernity, the celebration of “European achievement while concealing its darker side, coloniality.” I have taken modernity to heart, where I have focused too heavily on innovation above tradition/heritage, science and technology above indigenous knowledge, and individualism above collectivism.

As a partial outsider in the communities that were once my home, I must question how I can prevent the unconscious coloniality of the above ideas from clouding my observations when I return to Sierra Leone. Integrating more of my cultural and indigenous practices can decolonize my subjectivities and challenge the western conceptualization of progress.

Traveling to Kono District, Sierra Leone, for research this summer will undoubtedly raise a wealth of indigenous knowledge and help me to generate ideas for small and meaningful impacts in the area. I hope it will also allow me to “excavate deeper into the cognitive layers of [my] ancestors.” While in the USA, I have lost contact with my “Root Metaphors” – the unconscious

thoughts that “we use to frame other aspects of our meaning” – and I hope to rediscover them by returning to my ancestral home.

As I continue my Ph.D. study at CMU, I know my obligation to do more. I am acutely aware of the privilege I have been afforded, and I cannot allow it to cloud my judgment. Working to excavate my subjectivities will facilitate greater consciousness of the epistemologies that impact my designs.

References

- Baldwin, James (1961) Nobody Knows My Name, Dial Press.

- Lent, Jeremy (2017) The Pattern Instinct: A Cultural History of Humanities Search for Meaning, New York: Prometheus Books.

- Mignolo, Walter D. (2011) The Darker Side of Western Modernity: Global Futures, Decolonial Options, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

Knowledge that would be Useful : “3 P A”

“The reason there will be no change is because the people who stand to lose from change have all the power. And the people who stand to gain from change have none of the power.” Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli

The “3 P A” theory of hegemonic design holds that individuals who control power, privilege, politics, and access use their disproportionate influence to impose solutions on others. They are free to design spaces where they can extract resources from disempowered groups, relying on the insufficient autonomy within dispossessed groups.

“3 P A” has arisen from imperialistic prejudices against traditional cosmologies that are considered “primitive.” An obsession with progress dictates that Western society is future-facing; traditional civilizations in the global south are stagnant and only have a purpose when relegated to museums. It is a crucial node where the “colonial power matrix” is observable.

The ongoing colonial matrix of power is a complex entanglement of several intersectional hierarchies that affects all dimensions of social existence, impacting labor, gender, sexuality, and religious relations within nations, and Europe-not Europe, East-West, and modern-not modern relations between nations. This colonial matrix of power advantages the West by erasing alternative ways of being and knowing, thus homogenizing according to Western models.

Creating alternative imaginaries is the only way to displace the influence that “3 P A” still has over which individuals can design the future. Walter Mignolo defines the imaginary as “the ways a culture has of perceiving and conceiving of the world.” Therefore, if imaginaries are created that can compete with the hegemony of Western Modernity, a more pluralistic world will emerge where Western ideas are unlearned.

Pluriversal concepts were driven to the front of design’s attention by the release of Constructing the Pluriverse, edited by Bernd Reiter. Reiter’s team added depth to pluriversal ideas, surpassing previous colonial modernity critiques and considering pre-existing pluriverses. They documented

an array of non-Western practices within critical areas, such as the oral transfer of knowledge and stories in the West African context. This work has created a new “toolbox” for designs that dismantle the products of Westernization, like the power of “3 P A.”

“3 P A” is a tricky aspect to deal with when designing new spaces and solutions for Sierra Leone. I must acknowledge my positionality and privilege of holding all the “3 P A” attributes in some form or through my geopolitical position, professional background, and comparative wealth. Moreover, I must recognize that I benefit from a fourth “P”: patriarchy. I am in a family where I am the only son. I have seen countless instances where people will automatically take my word over my mum or my sisters, or how people can expect my women relatives to have a male figure to provide for them. With this privilege, how can I make sure I continue to seek ways to dismantle these “root metaphors” of power, privilege, politics, and patriarchy in my personal life and design practice.

References

- (2018) Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge, ed. by Bernd Reiter, Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Grosfoguel, Ramon (2011) Decolonizing Post-Colonial Studies and Paradigms of Political Economy: Transmodernity, Decolonial Thinking and Global Coloniality, University of California eScholarship.

- Mignolo, Walter (2009) “Coloniality at Large: Time and the Colonial Difference”, in Enchantments of Modernity: Empire, Nation, Globalization, ed. by Saurabh Dube, India: Routledge.

- Mignolo, Walter (2012) Local Histories / Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, and Border Thinking, Washington D. C.: Princeton University Press.

- Quinjano, A. (2000) “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America”, Nepantla: Views from the South, 1(3) pp. 533-580.

Building New Ontologies : The 7 Rules of the Zapatista Movement

The Zapatista Movement and its diverse, worldwide network immediately stood out as an applicable ontology when I learned of it this semester. This anthology notes the rules that guide the Zapatista and how they have and will tangibly develop my work.

The 7 Rules of the Zapatista when designing are: Lead by Obeying, Propose Don’t Impose, Represent Don’t Replace, Anti-power Against Power, Convince Don’t Defeat, Everything for Everyone, and Construct Don’t Destroy.

The most important rule for my work is Rule 7 (Construct Don’t Destroy) and Rule 2 (Propose Don’t Impose), which force us to create constructive options for stakeholders we design for. It also becomes of great importance when facilitating design interventions for indigenous communities by ensuring these interventions do not damage the pre-existing way of life but conserve it.

The 7 Rules of the Zapatista Movement offers some intentionality in generating ‘alternatives’ for new worlds in the pluriverse, preventing us from using our designs to pull indigenous communities into our pre-existing worlds.

As I move forward in my academic, philanthropic, and entrepreneurial careers, applying the 7 Rules of the Zapatista Movement will be crucial in stopping me from attempting to impose new designs that embody western hegemonic ideas. By acknowledging our own “3 P A,” while enacting the 7 Rules of the Zapatista Movement, we can enact or liberate new sensibilities that situate us to facilitate new interventions that are contextualized and localized to fractal environments.

Benefits, Burdens and Reclamation

While I cut my teeth in the design world, my work followed the Western epistemologies of Max Weber’s “protestant work ethic,” aiming to optimize the productivity of my designs with little care for the environmental and social impact of what I was doing. I focussed too heavily on the groups my designs could benefit from, with no understanding of the potential burdens I could add to indirect stakeholders.

Thankfully, a strong interest has developed in the epistemologies and ontologies of the global south as I continue my Ph.D. study at CMU. I started to understand the importance of “ways of being,” reflecting the” historical trauma” and background underlying my indigenous knowledge.

I have also begun to think about more tangible reflections of my indigeneity by considering the symbols and images that reflect my indigenous culture’s history and are applicable in my research. Artists and designers such as Michael Heizer have conducted groundbreaking work in reclamation art. Heizer’s Effigy Tumuli uses the indigenous American “mound building” techniques to create “geometrically abstracted animals.” Research and discovery of this traditional indigenous imagery can be leveraged to gain a greater understanding of the indigenous culture that has been displaced by Western hegemony. I hope to use reclamation art to add to Kumba Femusu Solleh work on the indigenous culture of the Kono people, adding further traditions to the Damby tradition that Solleh investigates.

Much work has been done by Eduardo Duran, John Gonzalez, and others into South America, a continent that has dominated the decolonial landscape. My research will look for ways African scholars can engage and be heard within decolonial design research and practice.

References

- Duran, Eduardo et al (2008) “Liberation Psychology as the Path Towards Healing Cultural Soul Wounds”, Journal of Counseling and Development, 86(3), pp. 288-295.

- Gorgi, Liana (1990) The Protestant Work Ethic as a Cultural Phenomenon, European Journal of Social Psychology, 20, 499-517

- Solleh, Kumba, Femusu (2011) The Damby Tradition of the Kono People of Sierra Leone, West Africa, Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse.

Buen Vivir And the Logic of the Capital

Translating as “good living,” Buen Vivir is a philosophy that design should work only to enhance the collective wellbeing of a community, treating all stakeholders with dignity and respect. Carrying respect in everything we do helps begin the path towards a pluriversal world because it becomes impossible for “othering” different communities.

By its nature, Buen Vivir denies the Western epistemology that the logic of capital must be followed at all times, as to do so would make human life a secondary concern. The capitalist system constructs itself around the maximization of productivity and a naive theory that doing so will enhance the wealth of everybody. Of course, capitalism has failed to guarantee prosperity for all it touches instead of creating inequality globally.

Despite its failures, Western capitalism and the profit motive have been entrenched by the accumulation by dispossession of the other. People now see the land in their localities as something to be exploited for maximum short-term profit, with little care for the damage done to the natural environment. Buen Vivir and its denial of the logic of capital has the power to replace the prioritization of short-term profit with long-term ecological and social wellbeing.

References

Calderon, Carlos (2018)

Thoughts on Cosmopolitan Localism and Cultural Entrepreneurship

Every year, Sierra Leone exports around 700,000 carats of diamond, yet Sierra Leone is still one of the most impoverished nations on earth, with a child mortality rate of almost 10%. These damning statistics, as well as my own experiences in Sierra Leone, have provoked me to explore disentangling the country’s resource wealth with its poverty and its invisible position within the international community. Cosmopolitan Localism is a significant thread that has emerged in my efforts in this space.

Cosmopolitan Localism is “the theory and practice of inter-regional and planet-wide networking between place-based communities who share knowledge, technology, and resources.” It proposes place-based solutions to deal with the need for subsistence in everyday life, whereby communities sustain themselves from the resources available within their localities. They may fulfill Max-Neef’s other nine universal needs within their more expansive Cosmopolitan Localist systems. These are the non-tangible needs for protection, affection, understanding, participation, idleness, creation, identity, and freedom.

Cultural entrepreneurship can help fulfill the non-tangible needs within a Cosmopolitan Localist system. It is a theory for designing nested webs of small and meaningful enterprises that consider the cultural and social fabric of the place they are being designed in. These designs can immediately impact their locality and have a wider influence by allowing other communities to appropriate the designs for their own context.

In a cosmopolitan localist system, nested cultural entrepreneurship networks can be applied to the natural resources space—freedom to steward their land, approaching it with reciprocity capitalism and a “seven generations ahead” mindset. Furthermore, as a Lakota farmer may organize a feast for the community when they harvest, ommunities may share surplus resources with others in a nested cultural entrepreneurship network

As I reflect on my exile from Sierra Leone, I realize the impact Cosmopolitan Localism and Cultural Entrepreneurship could have had on my own life. If Kono people’s need for sustenance could have been fulfilled from the resources available to us without relying on diamond extraction, the civil war may never have happened, and I may never have been forced to flee. Having my other needs fulfilled through Kono’s position within a wider Cosmopolitan Localist system will have changed my entire life trajectory.

References

- (2018) “Sierra Leone”, Kimberley Process, last seen 12/4/2021 https://www.kimberleyprocess.com/en/sierra-leone-0#2017

- (2019) “Sierra Leone – Under-five mortality rate”, Knoema, last seen 12/4/2021 https://knoema.com/atlas/Sierra-Leone/Child-mortality-rate.

- Kite, Suzanne (2020) “How to build anything ethically” in Indigenous Protocol and AI, Honolulu, pp. 75-84.

- Kossoff, Gideon (2019) “Cosmopolitan Localism: The Planetary Networking of Everyday Life in Place”, Centro de Estudios en Diseño y Comunicación,

What is Entrepreneurship through the Lens of Transition Design?

The current “wicked problem” within entrepreneurship is that it functions solely to put out fires created by systemic issues. Daniel Munoz notes, “we are designing within a problem-solving paradigm, where we do not see how we are creating new worlds when we design.” I can see this within my work that has been driven by the idea that Africa needed solutions yesterday and that I must play ‘catch-up’ without time to think about the broader implications of my work.

Transition design has utility in allowing me to step back from my entrepreneurial endeavors in Kono and consider steps to ensure that I stay true to the Kono people. Without analysis, my entrepreneurship will likely introduce fast solutions – western ways of being when contrary, I seek to preserve indigenous ways of being.

Leveraging transition design to improve my ethical intelligence as I engage in designing new interventions. Further research will unearth methodologies, but the Nuremberg Code is an excellent starting point. The Nuremberg Code is an essential test for new ideas, asking the following questions. Is the design or endeavor of benefit to society? Is it the only way? Do all actors consent? Is the risk proportional to the benefit? What harms are possible? How can these harms be mitigated? Only once these questions have been answered satisfactorily can I conclude that a business solution positively impacts a community.

A significant aspect of my research is the conversion of entrepreneurship to an academic design praxis. Embedding the theories of transition design more will prevent my business solutions from doing more harm than good, allowing me to understand the broader impact of my interventions beyond the contextual specificity that it has been created for.

References

- Cardoso, Daniel (2021) “Sculpting Spaces of Possibility: Brief History and Prospects of Artificial Intelligence in Design”, in The Routledge Companion to Artificial Intelligence in Architecture, ed. by Imday As and Prithwish Basu, Routledge: London.

- Shuster, Evelyne (1997) “Fifty Years Later: The Significance of the Nuremberg Code” The New England Journal of Medicine, 337, pp. 1436-1440.

In Situ Utilization

In situ resource utilization (ISRU) coined by NASA to in their quest to explore Mars. To evolve into a space-faring civilization, humanity must sustain itself using only the resources it can acquire on its destination planet. I have extrapolated ISRU as a means for localities to sustain themselves from the resources “in place.” Specifically, I aim to apply ISRU to Africa localities so that indigenous people can produce everything they need to fulfill their needs without relying on imports from the West.

In practice, ISRU would entail the gathering, processing, and using natural resources by indigenous African people from their natural environment to fulfill their locally specific needs. Doing so would require obtaining resources in a sustainable manner and the ability to manufacture products that Africa is currently dependent on the West for.

ISRU would unshackle the continent from the exploitative chains it has been kept in since the Berlin Congo Conference, allowing Africa to forge better connections. New economic power would come with respect on the global stage, and Africa could create policy and partnerships on its “own” terms. Internally, Africa would be free to explore internal designs and policy for the common good, defined by Fagence as “convenient, efficient, compatible” solutions that protect “minority interests.”

More ISRU practices in African communities would transform Africa for the better and most of the outside world because an independent Africa would facilitate the collapse of extractivist industries. The rest of the world would reap the benefits of reduced air pollution and the diffusing of the tense battle between Chinese and American Imperialism for African resources.

As my Ph.D. research continues, I will continue to research new ways for small and meaningful interventions that some African localities can sustain themselves from their resources. Transforming the whole continent in this manner is unlikely to happen in my lifetime, but aiding specific communities in their question for self-sustenance is a node to make a significant impact.

References

- Benaroya, Haym et al (2013) “Special Issue on In Situ Resource Utilization”, Journal of Aerospace Engineering, 26(1), pp. 1-4..

- Fagence, M. (2014) Citizen Participation in Planning, Amsterdam, Netherlands, Elsevier Science.

Small Meaningful Impacts

I began my academic journey overly optimistic. I had formed general ideas of the world’s “wicked problems” – poverty, natural resource exploitation, and others – and my quest starting my Ph.D. was to spend the next four years to come up with solutions to solve the world’s biggest problems. I hope to find a single solution to eliminate some of the problems I am grappling with. After learning the complexities of the problem spaces, I realize that I have four years to make a small meaningful impact in the problem space. The mindset flipped.

As my mind has matured through further academia, I have learned to find more realistic value elsewhere, namely in creating small meaningful impacts. Such designs would not change the world or solve the problem but could act as a node to change people’s lives in specific localities. These designs reform within pre-existing systems and do not carry the risk of societal collapse that revolutionary change may bring.

Hoping to revolutionize a system leads to designers becoming stuck in a “problem setting” mindset, obsessed with discovering “what is wrong and what needs fixing” over finding ways to fix the specific problems. Seeking smaller, more achievable impacts can grant designers with a “problem solving” mindset, benefiting from a much smaller aperture that allows them to capture the full complexity of the place.

Land reclamation projects in Sierra Leone are the perfect example of these small meaningful impacts, filling the dangerous and polluting pits left by mining and converting them for immediate agricultural use or to re-integrating them into nature. There is a substantial precedent of these projects operating successfully, with USAID alone supporting 662 such projects across Sierra Leone. NGOs such as RESOLVE have gone further than handing land back to owners in usable forms by using land reclamation projects to create areas of common land. Their cooperative projects with indigenous people have completed community rice farms positioned on reclaimed land and have helped thousands of Sierra Leoneans gain food security.

References

Thoughts on Technology and Ethics

I have experienced first-hand the corporate desire to create the impression of caring about their actions’ ethics while distancing themselves from anything that might challenge them to do business differently. “Bureaucratized expectations of professional behavior,” and they aim to “operationalize” ambiguous ethics exist solely to protect businesses from liability rather than making their practices any more ethical. Tech companies must start asking these questions intentionally before enacting decisions. What moral ethics drive this decision? Who wins and who loses in the process? And who has decided the standards we are applying?

An endemic failure to answer these questions has led to businesses “performing” rather than “doing” ethics. “Performing” ethics is expressed when tech companies attempt to “transform vagueness into precision through formalization,” allowing them to oversimplify the complex and make it marketable.

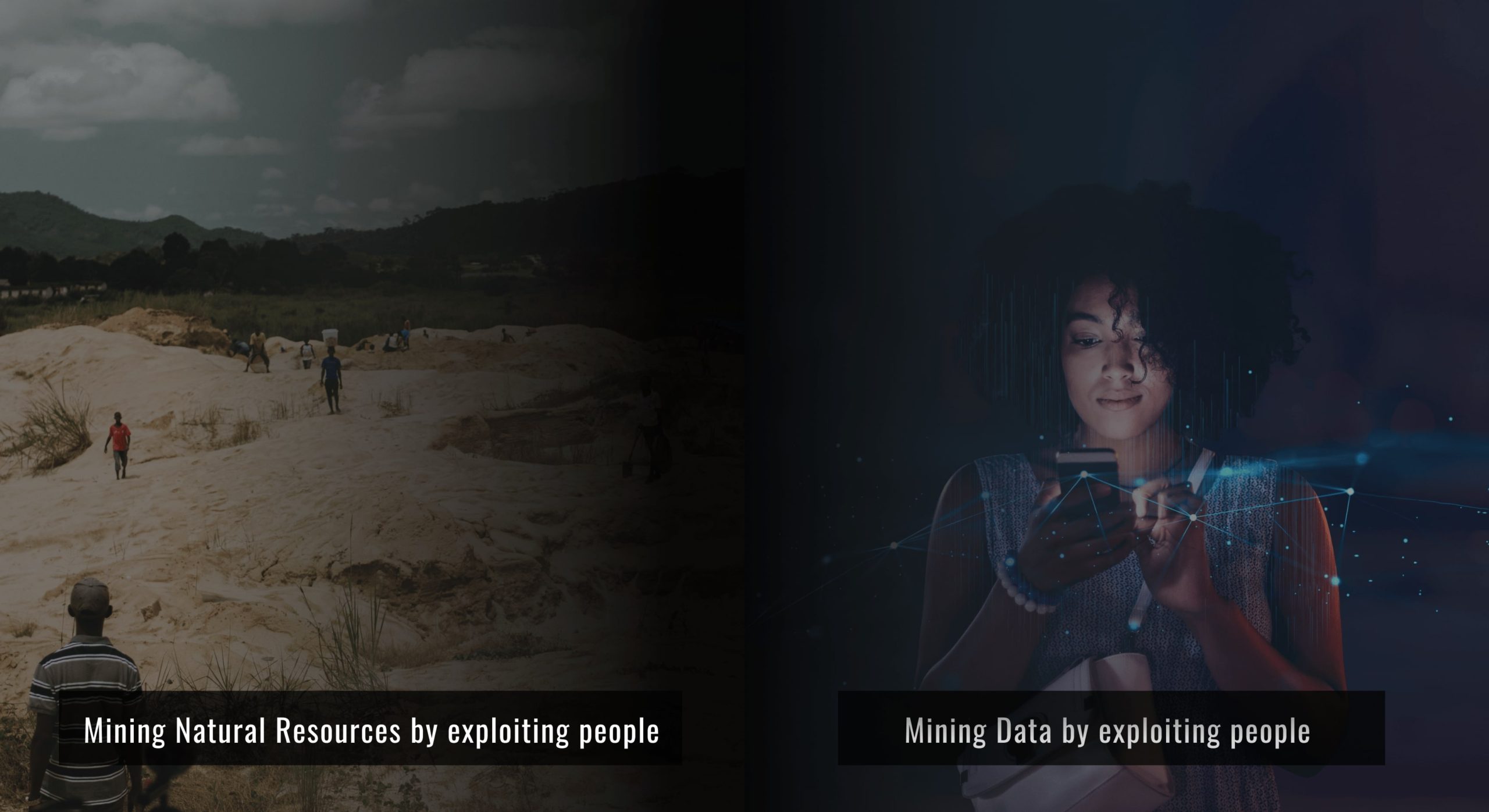

Tech companies practice this simplification every day that they fail to delve into their complex supply chains, which can take four years to understand. The scale of suffering and ecological collapse that occurs to sustain the extraction of raw materials and their conversion into finished goods would be unmarketable if Western consumers had the opportunity to understand the processes. But tech companies intentionally keep consumers in the dark to know only of a vague “other” in a distant land, and tech companies can create a sense of ethicality.

Design justice is desperately needed by the tech industry to be preserved while concluding their practices that exploit the environment and people. Further research is required to demystify these complex global supply chains to provide the transparency needed for questions of ethics to be asked of them. Where failures of ethics are found, design justice can be leveraged to convert these failures into humane practices.

Specifically, Suzanne Kite argues that “AI cannot be made ethically until its physical components are made ethically,” striking at the heart of consumer electronics that rely on the Earth’s resources and labor. She observes that reciprocity must exist at all levels of the supply chain for design justice to exist within them. Her indigenous inspired stress-tests, such as the Lakota idea that all ideas must preserve the land for “seven generations ahead,” could be transformative if applied to supply chains.

However, these ideas are only speculative, and we must acknowledge that tech supply chains are at the height of their vagueness. This raises a challenge to my professional background and interests, where I used AI, machine learning, and augmented reality to aid my design work. I cannot hide the role these technologies played in creating designs that benefited people’s lives, and I should not shun them in my future design work. I must weigh the positive social impacts of my designs for direct stakeholders against the negative social and ecological consequences for indirect stakeholders before using some aspects of technological solutions.

Reference

- Crawford, Kate (2021) Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press.

- Dove, Graham et al (2017) “UX Design Innovation: Challenges for Working with Machine Learning as a Design Material”, CHI ‘17: Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Hum

- Metcalf, Jacob et al (2019) “Owning Ethics: Corporate Logics, Silicon Valley, and the Institutionalization of Ethics”, Social Research: An International Quarterly, 86(2), pp. 449-476.

African Design and Development

Africa is seen in the West for its poverty by those who patronize it and its natural resources that cynics can extract. Western intervention is regarded as necessary to reconcile its troubles, with Africa receiving outside innovation and producing none of its own. De-colonialists have pushed back, developing a divergent perspective of Africa as a continent with rich ecosystems, insightful indigenous knowledge, and the resources that can sustain it. This anthology will focus on the role design plays in this context and technology as a case study. Finally, it will consider how African heritage can be preserved where new designs are introduced.

Design has always been integral in African culture, with archaeological discoveries of ancient artistic artifacts happening all over the continent. These include ornate soapstone carvings discovered in Kono. At an everyday level, traditional mud and wattle housing has proved effective enough for the local climate that rural Sierra Leonean housing design has changed little.

In recent times, African intellectuals have worked to create new African designs and raise the next generations of African designers. Ghanaian academic Lesley Lokko has begun an influential architecture school in Accra as part of this effort. The African Futures Institute will protect independent African knowledge and designs and “teach the global north how to embed diversity, equity, and inclusion in the heart of a built environment pedagogy.”

Design for Africa is more complex than teaching indigenous people design. Africa is a diverse continent formed of thousands of tribes and communities, and its lineage of epistemologies is complex. Ignoring this diversity would lead to designs inappropriate for some African communities being imposed upon them. The work of Pan-African scholars can help Africa to overcome the complexity by uniting the continent around intersectional benchmarks.

Achieving a level of intersectionality could be simpler than ambitious Pan-African projects if African communities are given the freedom to design for their contexts. Africans already utilized their localized specificity to appropriate and customize outside technology. The mobile phone has become a living artifact of the environment, choreographed for the environment, cultural, and economic conditions of the place. Tolu Odumosu’s chapter “Making Mobiles African” details the specific practices adopted for Nigeria’s localized specificity, such as “flashing.”

Appropriation of mobile phones illustrates what design for Africa is in contemporary times. It displays how an understanding of an African community’s complex structures and socio-anthropological factors – economics, materiality, culture, intelligence, citizenship, race, gender, sexuality, religion, media, and ecology – is required to create designs for that locality. The lack of understanding of this has led Western scholars to fail in unearthing the meaning of design in Africa at the detriment of African heritage.

References

- Odumosu, Toluwalogo (2017) “Making Mobiles African”, in What do Science, Technology, and Innovation Mean from Africa?, ed. by Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

- Raja, Amrita (2021) “Founding the Future: Lesley Lokko talks to AN about race, academia, and starting an architecture school in Ghana”, The Architect’s Newspaper, last seen 12/4/2021 https://www.archpaper.com/2021/01/lesley-lokko-talks-race-academia-and-starting-an-architecture-school-in-ghana

Research and Design Methods

Throughout my first semester at CMU, I have been introduced to many research methods that have utility in my work. This anthology details those that have been most influential in my work.

Methodologies

The structure of my research plans to follow Edmondson and McManus’ theoretical continuum of research: nascent, to intermediate, to mature. The continuum begins with exploratory and future-focused fieldwork that surfaces insights and opposition. In this nascent stage, the aim is to create “prepositions” for new research areas. These are then developed over multiple years to the mature stage, where the research is refined through repeated experimentation and observation. Continuing my first year of my Ph.D., my research methodologies fall into the nascent and exploratory category. These methodologies are detailed below.

Patchwork Ethnography

Creating an accurate ethnography of a locality from an outsider’s perspective is challenging. “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography” reconciles this by suggesting the use of short-term “rigorous” but “fragmentary” field investigations alongside long-term commitments to understand further and create ethnographies for the community. Patchwork ethnography understands researchers’ limited time available in localities and forces them to commit to generating better understandings of the ethnographic characteristics of the place.

Narrative Inquiry

Narrative inquiry discovers how broader structures have impacted people’s lived experiences within a locality. By recording these experiences, researchers can discover the nature of “wicked problems” within a community and better understand the designs that might be effective in that context.

Deep Listening

Deep listening is crucial for researchers working with indigenous communities because it prevents unconscious cultural biases and Western epistemologies from clouding the researcher’s judgment. By listening with openness and a willingness to learn, researchers can intentionally withhold all judgment and genuinely act as neutral observers.

“Entrepresearch”

In my first semester, I have also began to explore a new research methodology. My conceptualization of “Entrepresearch” has been inspired by Frederick Van Amstel’s “Perspective

Design.” “Entrepresearch” is an action-based design that combines academic design with entrepreneurship to develop alternative presents by delivering tangible solutions with an immediate impact tailored to the local context.

Collective Walking

Collective walking is the process of physically walking through significant places in a locality or within someone’s life. This practice varies in scale from walking through key performative sites, such as Selma Bridge, to walking through someone’s land. On the walk, the researcher is joined by individuals who exist within the space, allowing them to discover the role of the space in people’s lives before designing for it.

Cultural Probes

Using cultural probes gives indigenous people the ability to create a picture of their lives so that researchers can understand their socio-cultural experiences. They are invited to work with photography, diary writing, videography, radio, and others to document their experiences across various media, each giving them the opportunity to raise different perspectives.

Data Collection & Sensemaking

Composite Narrative

Once data has been collected, researchers may compare the experiences of many individuals within the same groups to identify critical similarities. These can be compiled into a single unifying narrative that can unearth shared motivations and ethnographies within a community.

Conclusion

These liberatory research methods and practices are perfect for assisting explorative designers, who may use them to discover “the most number of possible solutions or opportunities” possible. They will allow designers to create designs for countless new worlds that can dismantle pre-existing systems and design for transitions into the future.

References

- Choma, Joseph (2020) The Philosophy of Dumbness, San Francisco: ORO Editions.

- Edmondson, Amy C. and McManus, Stacy E. (2007) “Methodological Fit in Management Field Research”, Academy of Management Review, 32(4), pp. 1155-1179.

- Gökçe Günel et al (2020) “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography” Fieldsights last seen 12/4/2021 https://culanth.org/fieldsights/a-manifesto-for-patchwork-ethnography.

Extractivism and Modernity. Failed epistemologies for Africa

IIndigenous communities find it hard to break from Western epistemologies because modernity is everywhere. It displaces indigenous knowledge at all points of their lives, from the first time they learn “A is for apple.” Western education in indigenous communities amounts to the indoctrination of indigenous people into Western ways of being so that they believe Western capitalism is the only world available.

This hegemony of “westoxification” is a vital aspect of the Western epistemology, taking any attempts to create alternatives as fatally flawed “anti-modernism,” “anti-globalism,” and “anti-progressivism.”

Universal “westoxification” has trapped African localities within extractivist systems, resigning it to a position on “the dinner table, being eaten by superpowers.” Since the Berlin Congo Conference of 1884-1885, Africa has been regarded as little more than a resource bank to be robbed by superpowers to fuel their manufacturing industries. Ecosystems victimized by this theft buckle under the weight of extractivist damage, and indigenous people are economically coerced to toil and die in extractivist industries.

The latest boom in global commodities has provided new vigor for African extractivist industries, as the USA, China, and the EU compete for control. In this “new scramble for Africa,” extractive obesity has swelled to unprecedented heights, and Africa’s fragile ecosystems are struggling more than ever.

The “new scramble of Africa” has also further swelled the “ecological debt” owed by imperialist powers to Africa. “Ecological debt” sees Africa as the victim and the West as the beneficiary of extractive capitalism and reverses Africa’s debt crisis. It argues that Africa has paid its debts multiple times over in providing resources and the ecological damage that has come as a result, and therefore the West urgently must compensate the continent for the damage done.

Westoxification and the resultant entrenchment of extractivist industries in Africa have wrought untold ecological and social damage. The onus of reconciling this is twofold. Firstly, indigenous Africans must work to design alternative worlds to what the West has provided them, discovering ways to become independent of Western exploitation. More urgently, the West must recognize the damage it has brought to Africa through reparation. They must move away from coercive and insufficient aid and shift to paying the reparations they are obligated to provide.

References

- Deylami, Shirin S. (2011) “In the Face of the Machine: Westoxification, Cultural Globalization and the Making of an Alternative Global Modernity, Polity, 43(2), pp. 242-263.

- Greco, Elisa (2020) “Africa, Extractivism and the Crisis this of this Time”, Review of African Political Economy, 47(166), pp. 511-521.

- Warlenius, Rikard et al (2015) Ecological Debt: History, meaning, and relevance for environmental justice, EJOLT Report No. 18.

Digital Textiles and Reconciliation

An ignored aspect of all warzones is the actions of ordinary people to reconcile. Civil wars bring families and neighbors into violent conflict, so how do they learn to live alongside each other after the war? As a young child in Sierra Leone, every horror of the Civil War I witnessed preceded a heartfelt but ultimately unsuccessful attempt for reconciliation. Laura Cortés-Rico’s article on digital textiles and reconciliation adds to the reconciliation tools and provides an opportunity to reinvigorate the reconciliation attempts in Sierra Leone.

Reading Cortés-Rico’s article provides an opportunity for people like me in the reconciliation space. It focuses on textile craftspeople in Columbia, who use their talents to create physical objects to document and capture the conflict. Their work is inspirational and revealing of the role design can have in reconciliation efforts. It does seem far-fetched that creating physical or digital objects can reconcile tensions and even prevent conflict. Cortés-Rico tells us what the women of Choibá, Columbia told her was the main barrier to reconciliation: “Reconciliation is difficult because they [both the armed groups and the government] do not listen.” Difficulties with engagement from the militarily-minded are inevitable in reconciliation, but Cortés-Rico’s proposals still fill me with great hope. Her proposals help us to start asking how artifacts can be generated to foster a mutual understanding across violently opposed ideologies.

Inspired by Cortés-Rico, I came up with two activities that may have a role in Sierra Leonean reconciliation. In her article, Cortés-Rico describes the development of a “collective living lab” pushing for imaginative participatory design activities for people could engage in. She named hers after the Quechua term for meeting with others in the community to carry out collaborative work for social purposes. Having created the space, Cortés-Rico used “hackathon” and “make-a-thon” to inspire people from opposition social groups to cooperate in friendly competition.

These events could be perfect for the Sierra Leonean reconciliation because of how conflict emerges in the nation. The leading cause of instability is tribalism, whereby people live and work largely separately from people in other tribes. Separation prevents trust from arising and makes it too easy for people to dehumanize others. Cortés-Rico’s work has shown that imaginative participatory design activities perfectly deal with these issues. She found that participants opened up to each other through non-directive suggestions and displays of vulnerability. Individuals that had conflicted were able to show “confusion” and “care” to each other for the first time (Laura Cortés-Rico et al, 2020).

If imaginative participatory design activities are successful, a host of other opportunities for reconciliation will open up. If showing vulnerability and care works, what other activities will successfully engage people’s sense of care? And on a broader scale, what shared thinking and sensibilities can be unlocked through the process of making?

The other activity I came up with after reading Cortés-Rico’s article centers around the idea of “encountering.” She explains it with three key aspects: “the role of the body is fundamental, “one can encounter others through acknowledging her/his movements”, and “encountering takes time.”

The concept of “encountering” centers around Maria Puig de la Bellacasa’s ideas of touch: “when bodies/things touch, they are also touched.” De la Bellacasa draws us to the vulnerability associated with touch. If we are directly touching another, we are risking our health to their potential for violence, and if we touch something they have made, we are putting trust in their craftsmanship.

An “encountering” based activity created by Cortés-Rico’s team that fulfilled these requirements was the “Put Yourself in Someone Else’s Shoes” project. Participants from the textiles community would make the parts for shoes, and while doing so, think and record the “stories that are associated with the paths they have walked to move forward through the conflict.” Once completed, the materials are packed and sent to members of other communities, who then assemble the shoes and take a walk in them while listening to the recordings of the textile craftspeople’s war experiences.

The activity was time-consuming enough to be meaningful, while still being a tangible bodily experience that forced participants to think of the experiences of others. But, Cortés-Rico also reflects on what the activity can tell us about the process of reconciliation more generally. She notes that encounters for reconciliation are not limited to “static” physical encounters. As participants walked in the shoes made in cooperation with another person who used to be an enemy, speaking to each other through digital recordings, an encounter was made between two communities at a specific time. Yet the fact that participants did not need physical proximity to have a successful encounter makes this activity ideal for areas where travel is difficult.

Cortés-Rico’s exercise is an interesting one because it brings in two layers of touch. The most apparent form of touch is in the direct contact with the shoes, made in collaboration with the other community. But a more discreet yet still useful sense of touch is secured by the digital recordings. De la Bellacasa is well aware of the role technology can play in replacing touch with “technotouch” for the geographically separated: “technology is bringing the neglected sense of touch into the digital realm”. Of course, to listen is not to touch, but de la Bellacasa speaks of “touching visions” which can take the role of touch. Therefore, to hear can replace touch, so long as the sounds are touching enough.

While these activities will show themselves to be successful in the context of post-war reconciliation, they could also have a role to play in my research area: artisanal diamond mining communities in Sierra Leone and their consumers. “Encountering” between the consumer and the miner is currently impossible because people buy their diamonds from jewelry stores, that in turn, buy them from cutters in the West. When a consumer puts on their diamond ring, they are absurdly distanced from the miners.

So what will creating encounters between miners and consumers achieve, and what will it look like? ”Encountering” will open up a dialogue between the consumer and the miner as they learn to acknowledge the lives and movements of the other. It could also help develop new ways to tell the stories of diamonds digitally. Most optimistically, and only if a substantial proportion of consumers have encounters with artisanal miners, the industry may listen and engage.

“Encountering” is an elementary idea, creating the possibility for cultural artifacts to be used to tell a story, facilitating reconciliation. Could the simple shovel or shaker give artisanal miners a voice, meaning they will finally be listened to as victims of extractive capitalism? Artisinal miners can easily gain the tools to be heard; now, they need industry and the consumer audience to listen to them.

Mobile Phones and Appropriation

Africa is a space seen as behind the industrialized West; a continent whose problems must be solved through Western intervention. It is a framework that draws Africa as a recipient rather than a giver of technology and progress. And this appropriation of Western technology helps the continent to move up the developmental ladder. Theories of Decolonilaity challenge this implicit superiority of Western knowledge, and attempt to push back on Western design as the default design.

These ideas are powerful but are potentially misguided. They draw the thought and design of the Western world and the global south as separate, without any influence on each other. They completely ignore the potential that all Western technology is inspired, at least in part, by designers and thinkers in the global south. If an idea originated in Africa, separate from Hellenistic thought, and then was made mainstream in the West, would we remember its African origin?

In my doctoral research, I have worked extensively to unearth a lineage of thought back to African thinkers. Such work is needed to bring out and credit ideas with an African origin and will form a substantial aspect of the effort to decolonize design through understanding our contribution to western thought.

These ideas are relevant not only for technology with traceable origins in the global south but also for Western technology that non-Western communities have appropriated. The nature of this appropriation has allowed communities to travel a different technological path to the West. To take the communications industry as an example, Westerners popularized telegram and landline technology long before the cell phone became widespread. A different development path came in West Africa. The landline was never popularized, with only the wealthiest having access to a technology that quickly became obsolete. Instead, African communities used Western communications technology only when the cell phone became accessible because it could be appropriated to fit their needs.

The concept of appropriation is interesting because it goes much further than to suggest that communities in the global south borrow both the technologies and the usage patterns of Westerners. Instead, appropriation is the point at which an object ceases to be a commodity. The holder gains new ownership where they manipulate the object to function uniquely to their context (Silverstone and Hirsh, 1992). Only once this appropriation has occurred will the object become properly usable in that specific locality (Oudshoorn and Pinch 2003, 12).

This “localized specificity” is not only about how we use our devices. When a business adapts the design of their product to fit into a locality without people having to appropriate it, they see incredible success in making sales to new communities. To take Coca-Cola as an example, they began their iconic Santa Claus adverts in the 1920s, which continue to this day. Having adopted a worldwide cultural icon to fit their brand, Coca-Cola adapted to several “localized specificities” accounting for part of their sensational success.

Few brands have harnessed “localized specificity” to such effect, and it is still a term that better fits the appropriation of technology. The rapid adoption of cell phones by African people is an incredible example of this appropriation. In my birth country Sierra Leone, the demand for a cell phone has flipped Mazlow’s hierarchy of needs, with people prioritizing them over access to food and shelter. It is a change necessitated by the limits of $1.25 per day that 60% of the people live on. Oluwalogo Odumosu’s study of this phenomenon is fascinating, giving us an understanding of the “cultural and epistemic processes” that explain the success of the cell phone in Africa.

Odumosu uses the case study of Nigeria, and many of his observations are similar to my own from Sierra Leone. When new technology comes to a new community, it must adapt to the “localized specificity” of the area. Implementations must be conscious of the “place”, its people, their heritage and cultural behaviors, politics and geography, and economic conditions.

How a community appropriates “technologically analogous” devices for their “localized specificity” alludes to unique “social histories” and “socio-cultural niches” (Ito, Matsuda, and Okabe 2005, 1). By investigating user behavior, a story emerges of not only a community’s relationship with technology but of the place and society in question.

To paint this picture, we need to understand the constitutive appropriation of technology in a specific context, or in my case, how Sierra Leoneans have reconfigured the meaning of their cell phones to match the economic conditions, cultural practices, and situational placeness in a given time. As Odumosu also noted, many of my relatives have 2-3 phones, each having different coverage, battery life, and credit at any given time.

A choreography of usage that I observed arose from using a different device depending on the criteria of usage required at a specific time, and significantly the economic context of Sierra Leone. The practice of flashing is a commonplace reflection of economic realities. If somebody uses a cell phone without credit or the economic ability to “top-up”, they will end the call as soon as a connection is made. Having seen a missed call, the recipient will call back, transferring the cost away from the initial caller.

With technology usage patterns being significantly different from the West, networks must be established and maintained differently. Practices such as flashing bring in a uniquely high strain on infrastructure without generating any additional revenue. Western engineers cannot understand these needs, and therefore new engineering cultures are developed by locals. With insiders maintaining the network, everything but the device itself are independent of Western design.

The African cell phone is a fascinating case study of constituted appropriation. It is an object that has been choreographed to fit different environmental and economic conditions. The object I observed in Sierra Leone existed as a part of a group of devices, each with a network that was usable in certain areas but not another, purchased based on the cost and availability at any time and used conditionally of the battery life available.

The fascinating insights of Odumosu of mobile phone usage in Africa, corroborating my observations in Sierra Leone, provoked me to think more about constitutive appropriation and its utility in the natural resources space. How could new technological interventions for the mining industry, such as manufacturing, AI, and VR, be appropriated “for”, “by”, and “of” the people’s cultural practices and their ecological needs? What about them will need to be specific to the Sierra Leonean context? And how then might that create unique natural resource empowerment opportunities?

These are questions that I will have to wrestle with over the coming years, where I will constantly redesign my interventions and theories. Flexibility and self-interrogation will be required to solve real Sierra Leonean problems as they evolve. Within this approach, the “constituted” technological appropriations for natural resource empowerment must still reflect the cultural materiality and topography of Sierra Leone. Like all nations, it has its own social, political, and infrastructural peculiarities, leading to “instrumentally dissimilar” results.