Assignment 1: Mapping Wicked Problems

Collaborators: Fas Lebbie | Tasha Russman | Serena Wang

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

Older adults in Pittsburgh, PA, suffer heavily from the wicked problem of isolation, an issue characterized by its highly complex and pervasive nature. As older adults’ health declines, they simultaneously become increasingly isolated and lonely, contributing to further barriers to their overall wellbeing. For example, healthcare literature cites ample evidence linking loneliness to a higher risk of dementia and other severe health conditions. In Pittsburgh we see this, and other alarming trends in the midst of a $631-million budget shortfall that has left health and social care systems poorly equipped to provide the standards of care that the elders in our community need.

The isolation of older adults has been steadily growing within the context of the recent COVID-19 crisis. This, in turn, badly impacted Pittsburgh’s older residents who both died at a higher rate than expected and were more likely to become isolated because of care home visiting restrictions.

In mapping the wicked problem of isolation amongst older adults in Pittsburgh, we attempt to explore the complexities of this issue at depth, highlighting relationships between these factors and others, and shedding light on that which has caused and exacerbated them.

PART I: PROCESS

1. Establishing the Themes within the Wicked Problem

1.1 Start with STEEP

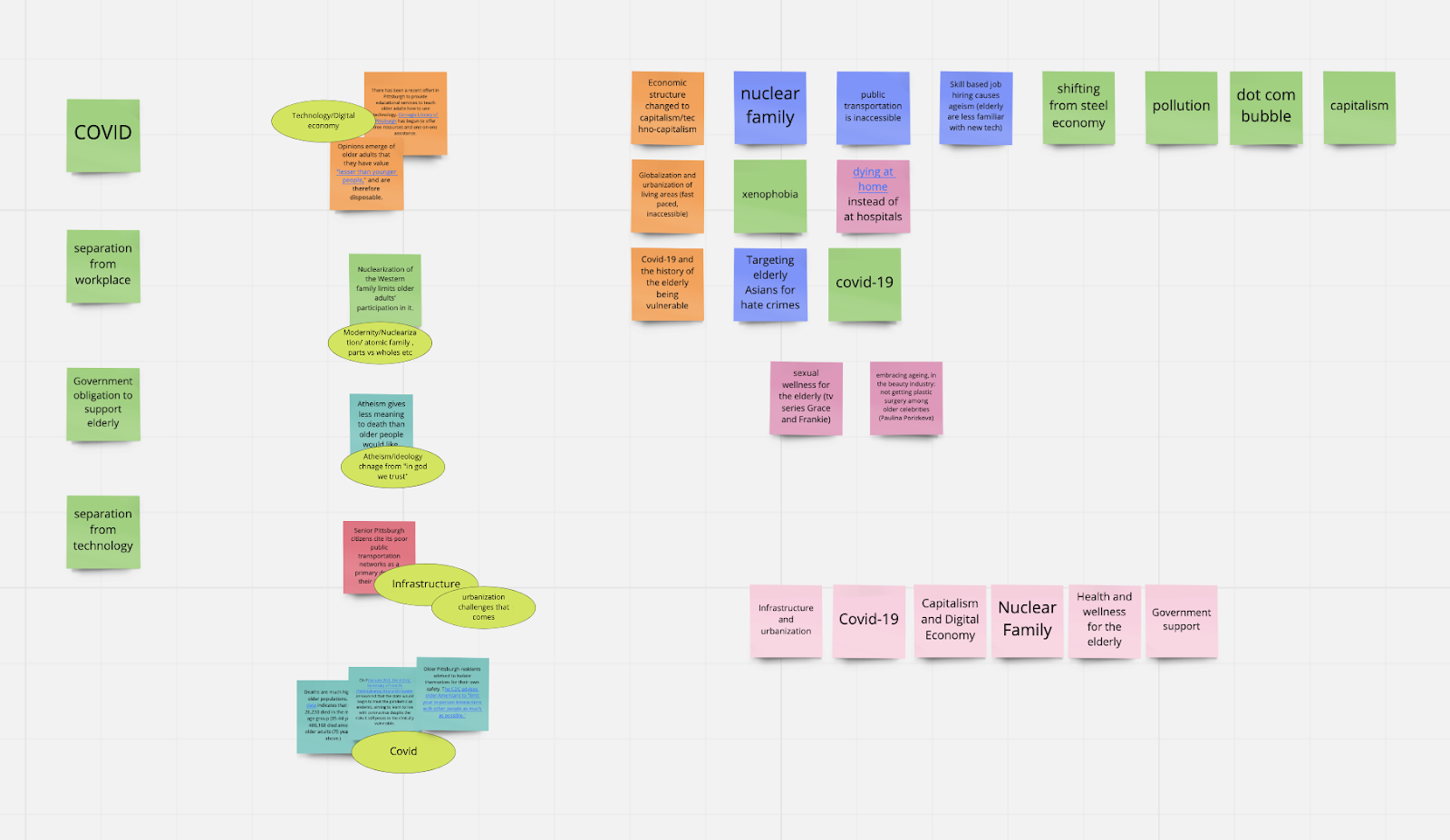

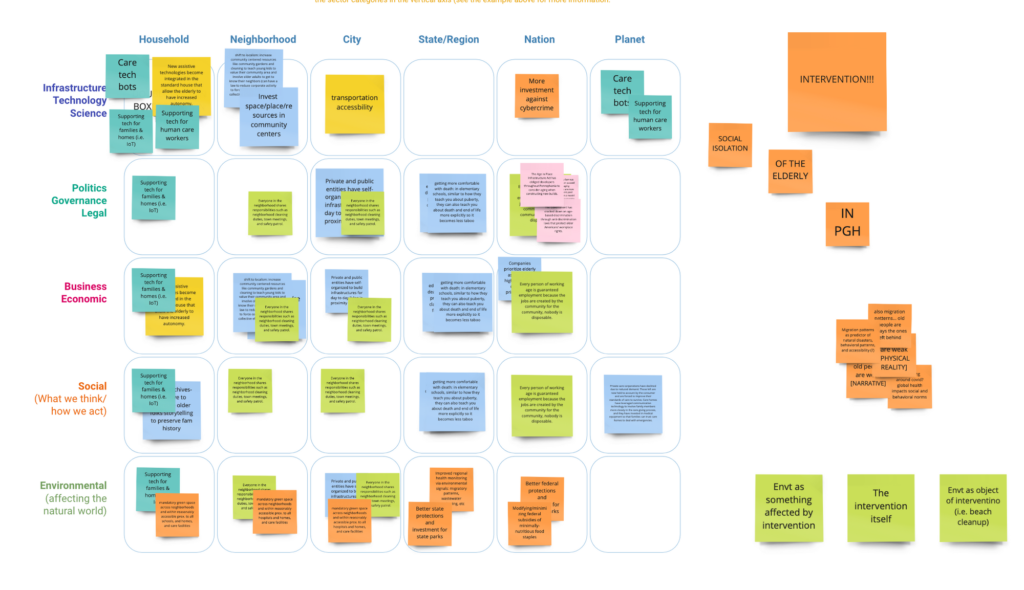

Our process for mapping the wicked problems of isolation in older adults in Pittsburgh was thorough, with each stage providing further depth to our analysis. We began at the surface level by researching the isolation of the elderly according to the STEEP framework: social, technological, economic, environmental, and political. This allowed us to identify key themes, which paved the way for us to dive deeper into the problems associated with the isolation of older adults in Pittsburgh.

Our process for mapping the wicked problems of isolation in older adults in Pittsburgh was thorough, with each stage providing further depth to our analysis. We began at the surface level by researching the isolation of the elderly according to the STEEP framework: social, technological, economic, environmental, and political. This allowed us to identify key themes, which paved the way for us to dive deeper into the problems associated with the isolation of older adults in Pittsburgh.

1.2 Identify Key Themes

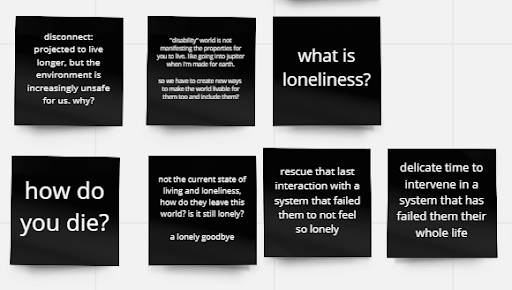

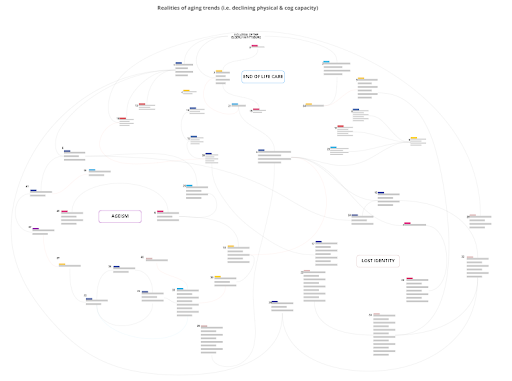

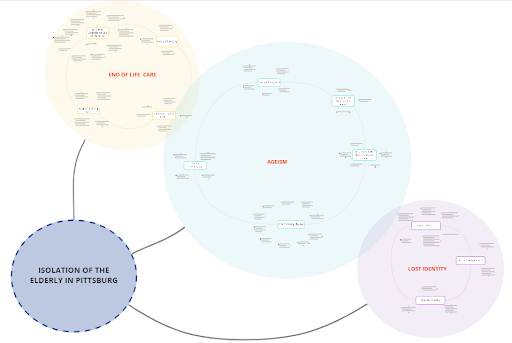

Our team met again to review the results of our primary research, where we consolidated data into key themes: ageism, capitalism, elder abuse, health decline, demographic change, identity, and COVID-19. Drawing out key themes gave context to the scope of the wicked problem; comparing them permitted the team to define the most salient themes (seen below, marked in black) that would serve as an initial framework to explore at greater depth. Emergent questions from the research included how do you die?, Are older people generational misfits?, What is loneliness?, and others. **Ultimately, further adjudication and analysis surfaced three major themes that define the experience of isolation among the elderly in Pittsburgh: 1) End of Life Care, 2) Loss of Identity, and 3) Ageism.

Before diving deeper into these elements of the wicked problem and mapping it, the final step was to come up with highlights from our work so far. These highlights were established as essential nodes to focus on as our work developed. Examples included making the research more Pittsburgh specific, showing the diversity of dying and the consequences of dying alone or in the company of family. Furthermore, we established crucial threads that most of the research would center around. These included “accessibility,” “socioeconomic status,” “healthcare,” and “loneliness.”

1.3. Review

The final step in our first phase of research was to take a step back and reevaluate our findings within the context of our original research focus. Isolation of the elderly is an issue endemic to much of Western society and indeed, much of the world. Within this context, and especially as we were working from under the shadow of the continued COVID-19 pandemic, it was important to ensure that our research was accurately situated to portray an accurate picture of the local and present landscape. We went back to the research, discussed again, and marked items that might require further attention.

2. Build the Framework

Confident in our approach, we were ready to visualize our framework, and began exploring how we could best map our findings in a way that would clearly communicate our own ideas, and inspire others to dive in, potentially generating their own.

2.1 What factors are important to communicate?

We began by considering the criteria that our map would have to fulfill. The first was to ensure our map effectively showed how our factors were aligned within the STEEP framework. We created a key, assigning a color to each STEEP category so that readers could immediately determine whether an element was social (pink), technological (yellow), environmental (light blue), economic (dark blue), or political (red).

The other criteria was to create our map with four critical tools: Causal Loop, Conflictual Relationships, Interdependencies, and Affinities. The facets and importance of each are summarized below.

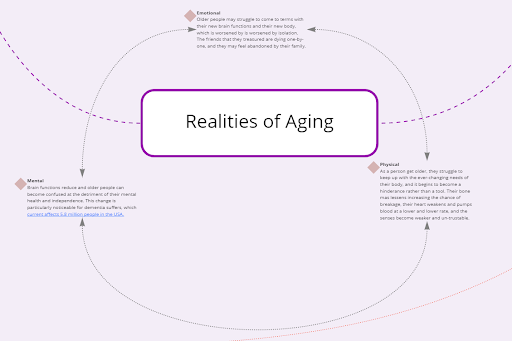

Causal Loops are used to display the inter-related causality between factors. When factors cause each other, have the same causation, or work together to cause something, we drew arrows connecting all of the factors to demonstrate the cyclical nature of their relationship. For example, with our “realities of aging” sub-theme, we determined the factors in the causal loop should be mental, physical, and emotional, all of which contribute to the aging process.

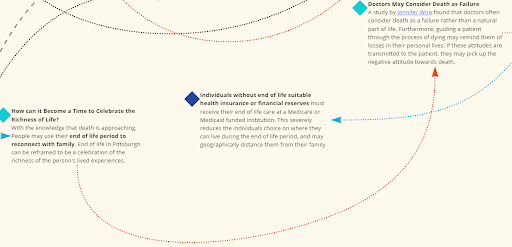

We generated three types of causal loops: conflictual relationships, interdependency, and affinity. We used Conflictual Relationships to demonstrate when factors were at odds with each other, each being fundamentally contradictory to the existence of the other. For example, we mapped the opportunity for end-of-life to be a chance to celebrate the richness of life, with the tendency for doctors to consider death a failure.

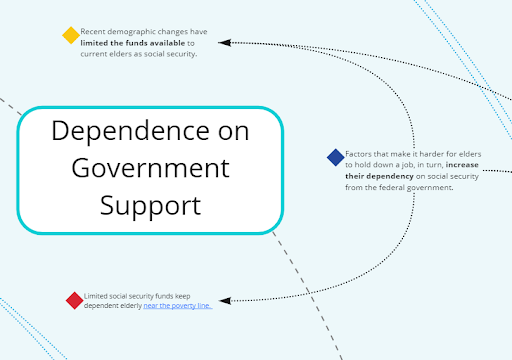

Another essential mapping tool was Interdependencies, with which we showed how factors build on each other to create a larger impact. For example, we created the triple-noded interdependency surrounding our “Dependence on Government Support” sub-theme. We showed how older adults struggle to hold down a job, and rely on social security. However, this social security is insufficient to protect older adults’ well-being because of funding shortages and demographic changes.

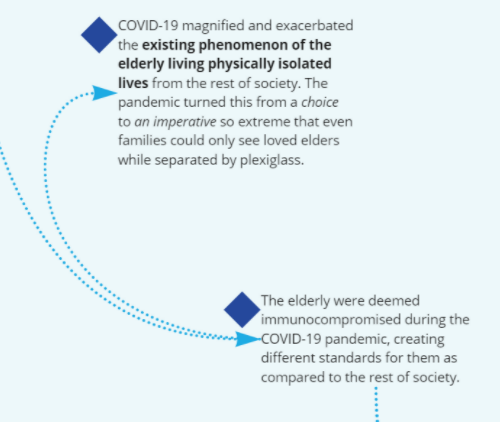

The final element of causal loops was Affinities, showing how nodes can exist within each other. For example, we deemed the immunocompromisation of older adults to be a node within how COVID-19 has further isolated the elderly. This is because immunocompromisation has led older people to have different standards than the rest of society. To display these, we drew sea-green lines between the two nodes.

Outside of causal loops, we situated some of the other wicked problems that colleagues were working on, to show how they are interdependent with isolation of the elderly in Pittsburgh. We mapped this by placing the wicked problem inside a diamond, and then connecting blue jagged lines between the wicked problem and the particular nodes that were most relevant. We connected “Poor Air Quality” to the hazardous environment of Pittsburgh and the resultant desire of the elderly to move into rural areas which are more disability friendly and have cleaner air. For “Lack of Access to Healthy Food”, we connected “limited social security funds” which have impoverished many older Americans and meant they cannot afford nutritious food. Next, we connected the wider problem of “Lack of Access to Affordable Healthcare” to the inability of the elderly to stay healthy and mobile. Finally, we attached “Lack of access to Education” to the monolithic view of the elderly, and the assumption that they will not want to participate in lifelong learning. In doing so, we were able to show the relationship between isolation of the elderly to the multitude of other wicked problems in Pittsburgh.

With these tools at our disposal, we were able to begin placing our key ideas onto a large-scale map, with our key on the side to make the meaning of our mapping clear.

2.2 Pivot

After substantial and comprehensive research, we finished our initial placement of ideas onto the map, centering nodes around our three main themes. We were generally satisfied by the result, which clearly expressed each of the three key themes, their contribution to the wicked problem of isolation of older adults in Pittsburgh, and their connections with each other by displaying Causal Loops, Conflictual Relations, Interdependencies, and Affinities across and within the themes. However, we did not feel our map told the story of how the themes were connected, building upon each other to form the holistic experience of the elderly in Pittsburgh. We wanted to create a system whereby individuals could establish the narrative with a single glance.

We needed to take a step back from the research, access what we had found, and design a map that told the story of how elderly Pittsburgh residents become isolated. We discovered that isolation of older adults generally follows the same progression from someone’s loss of identity to them facing ageism and then having negative experiences of end-of-life care. Each of these factors were clearly connected back to isolation of older adults.

PART II: CONTENT

LONELINESS AMONG OLDER ADULTS: THREE MACRO THEMES

Having established our final means to tell the narrative, we were ready to map out the exact nature of the wicked problem. Beginning with our three macro themes, we then defined sub-themes within them and used nodes to provide additional detail.

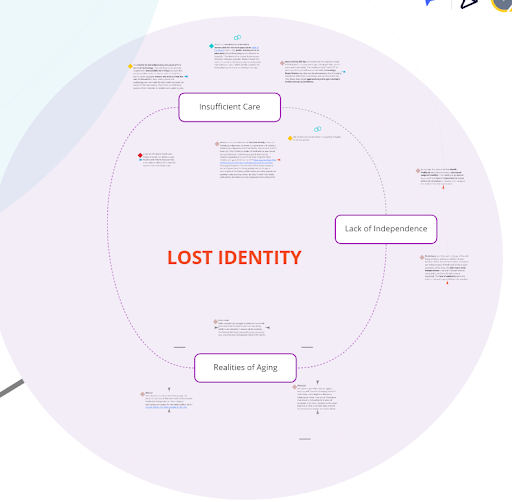

Theme 1: Lost Identity

A WIDENING ENVIRONMENTAL MISMATCH

Underlying the constructs in our map is the reality that people change as we get older; whatever social adaptations may or may not accompany the aging process, the fact remains that our physical, mental, and emotional selves evolve over time. Indeed, much of the complexity we find around perceptions of the elderly stem from the nature of an individual’s identity, and the extent to which it matches the changing realities in/around them.

One of the hallmarks of the transition into “older adulthood” is that it represents decline from long-held perceived norms; until that point, most chronological evolution has represented growth and/or continuity. This transition is different because, in general, we meet it with resistance. A significant outgrowth of this trend is that our elders experience a profound loss of identity: those who embrace the transition find themselves leaving behind the life to which they’ve grown accustomed. Meanwhile, those who treat their identities as static find increasing dissonance between the narratives they tell themselves and feedback from their daily lives. Both cases lead to a loss of the person they once thought themself to be, which can be a lot to swallow. So, while this transition can cause isolation in-and-of-itself through the inevitable changes it causes, it can also promote feelings of depression, a symptom of which is further isolation.

Our research showed a plethora of immediate implications of such “realities” including a decrease in mobility, cognitive function, and mental well-being, each of which contributes significantly to the characteristics, abilities, and activities that together make up a person’s sense of self. In Pittsburgh, these issues are each exacerbated by the nature of the environment, which is largely not designed for anyone whose needs are outside of “the norm.” That is, while much of the elderly population may have once fit the mold around which the city was built, they no longer find themselves enjoying the same environmental fit.

Unfortunately, this mismatch isn’t just limited to the built environment; it also extends to the technology that could otherwise help bridge the gap. Hardware and software designed for the needs of the elderly is few and far between, and is often incompatible with current technology because the elderly represent such a low priority in the development process. Elders could overcome this if resourced with adequate human support, however, they rarely have access to the care they need.

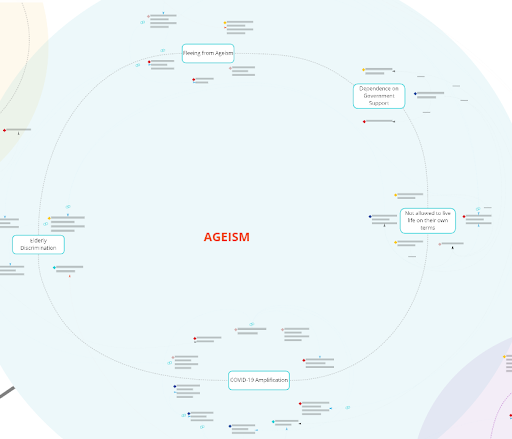

Theme 2: Ageism

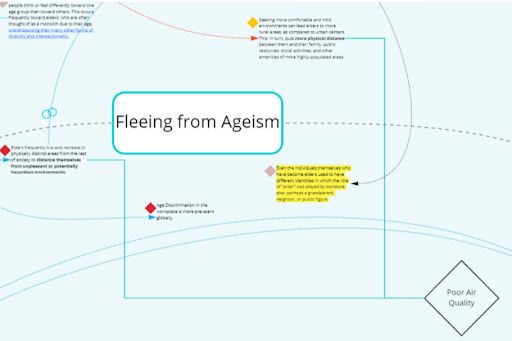

These areas where identity is lost through excessive levels of support lead to a lack of independence, and insufficient support, which leads to isolation, has been worsened by ageism in Pittsburgh. Ageism is a form of discrimination whereby people think differently about one age group. In “Ageism: A Foreword,” Robert N. Butler argues that there are three aspects to ageism against older people: “prejudicial attitudes towards the aged,” “discriminatory practices against the elderly,” and “institutional practices and policies which… perpetuate stereotypic beliefs about the elderly.”

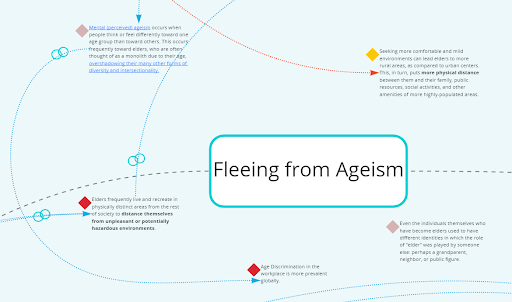

We divided our discussion of ageism into the sub-themes “Elderly Discrimination”, “COVID-19 Amplification”, “Not Allowed to Live Life on their Own Terms”, “Dependence on Government Support”, and “Fleeing from Ageism.”

Our elderly discrimination sub-theme examined the common narrative that older people are weak, frail, and dependent. These attitudes are common and prevent more senior people in Pittsburgh from living as they wish. They may reduce their caregiver’s allowance for them to be independent and make it near impossible for them to gain employment should they wish to do so. In an investigation into ageism and labor markets, Justyna Stypinska observed that modernization has dramatically altered the workplace structure to be less suitable for older people and perpetuated Mark Zuckerberg’s belief that “young people are just smarter.” Therefore, discrimination is a point where the elderly are treated as a monolith which ignores the intersectionality and diversity of ability within the older population and prevents them from playing any valuable role in society.

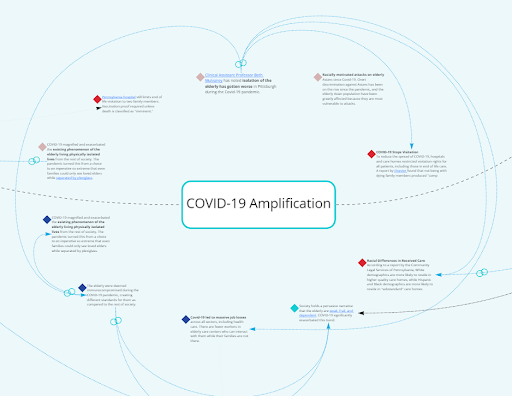

Ageism is also the first point at which COVID-19 emerges as a crisis point, profoundly exacerbating ageism and how it isolates older people in society. The physical isolation of the elderly turned from a choice to an imperative when it was a necessary means to preserve their health. This was seen immediately in official advice for Pennsylvania when the Department of Aging advised older Pittsburgh citizens that they should “stay at home as much as possible.”

Next, we examined how the elderly are not permitted to live life on their own terms. We identified an array of nodes that prevent the elderly from doing so, such as the likelihood for older adults to be limited by technology, the rarity for inclusive paradigms to take the elderly into account, and the expectation that older adults will not participate in society.

While older adults are kept out of the workplace and from becoming a functioning part of the economy, they are forced into dependency on government support. However, social security funding has been cut heavily throughout the USA, keeping them close to poverty.

This combination of factors can provoke older Pittsburgh citizens to leave the city searching for more rural areas of Pennsylvania, believing that these will grant them more comfortable and mild environments where they can live without discrimination. However, moves like these may make them more isolated from their families, less able to seek support, and can disconnect them from the city they have lived in for most of their lives.

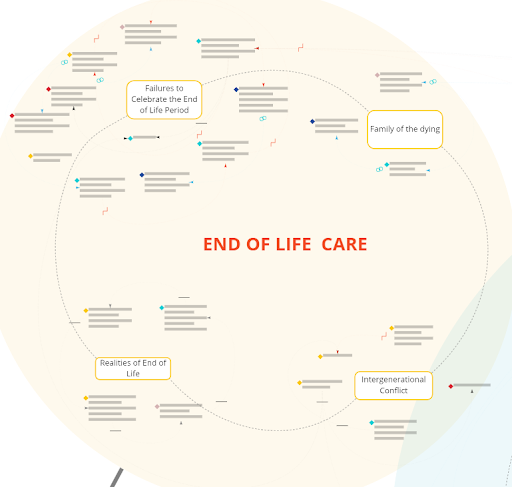

Theme 3: End of Life

The final aspect of an older Pittsburgh citizen’s life is their experience of end of life care, which our mapping of the wicked problem showed that they usually enter into with little of their original identity left and having experienced intolerable ageism. We began this section with a sub-theme on the realities of end of life, considering the older person’s experience and their family from diagnosis to death. Once this was complete, we began to map this final aspect of the wicked problem by dividing it into the sub-themes “Intergenerational Conflict”, “Family of the Dying”, and “Failures to Celebrate the End of Life Period.”

For our family of the Dying sub-theme, we considered the high impact of accompanying a family member into death on people’s mental health. Most notably, we engaged with a study by Siew Tzuh Tang that found depressive symptoms are substantially higher amongst people that provide end of life care to a family member. We then gathered insights on the resources available in Pittsburgh to reduce this impact, such as the Jewish Community Center’s “Aging Mastery Program” which guides attendees through their caregiving journey.

Another significant sub-theme looked into the points of conflict at the end of life period, particularly between the older individual dying and their younger family. We discovered that growing atheism in the USA and Pittsburgh amongst young populations is leading to a reluctance to give meaning to death. While 65% of Pittsburgh residents are religious, Pew research has found that Americans are 9% less likely to be religious than their parents. Simultaneously, older Pittsburgh residents are likely to attempt to reconnect with religion.

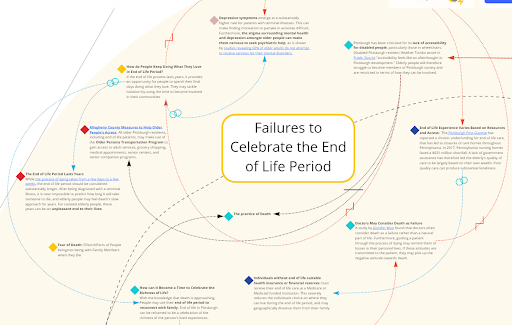

The final sub-theme built on from this difference, by honing in on the more pressing failure to celebrate the end of life period. We discovered that the end of life period takes years, not days, and is a significant stage within people’s lives. It could be harnessed to help them celebrate the richness of their life and share meaningful moments with their families. However, we identified nodes that prevent older adults from being able to enjoy their end of life period. A striking barrier emerged from the medical community, with a study by Jennifer Woo that found doctors tend to consider death a failure, making it impossible for patients to accept it is approaching. Secondly, end of life patients see much higher cases of mental illness than the rest of the Pittsburgh population, and they are most likely to struggle to access the proper help. Studies have revealed that 60% of older adults do not attempt to find support when they need it because of the stigma surrounding mental health problems within that demographic. Finally, poor standards of care often mean that older adults cannot even be comfortable, let alone take part in activities that will tackle their growing isolation.

Therefore, the end of life period is a valuable final opportunity for older adults to extract joy from life. But because of the above mentioned realities and sub-themes, this opportunity has twisted into a driver of isolation of the elderly up to the point of death.

CONCLUSION

Mapping the wicked problem of isolation in older adults in Pittsburgh was a productive activity that generated valuable insights into how the wicked problem develops as the aging individual draws closer to death, showing which themes within the wicked problem are consistent throughout the person’s experience.

Most notably, COVID-19 proved to be a significant crisis point that had brought many of the prominent themes that were previously invisible onto the front pages. Isolation, for example, was one of the most heavily exacerbated. We also discovered that, across all stages, older Pittsburgh residents are coming into conflict with their families. This is particularly tragic as the time aging people can spend with their families is rapidly running out.

Although these themes were consistent, they were experienced more intensely at specific points. For example, conflict with family does not reach a crisis point until ageism is experienced, forcing the older individual away from their families and into rural areas. Similarly, the emotional toll of aging on the aging person’s family is most severe the closer the person is to death.

Our map also showed the deep and complex connection between the isolation of the elderly and other wicked problems in Pittsburgh. Most notably, we saw how poor disabled access and care systems at a point of collapse further isolate the elderly by giving them few opportunities to exist alongside the wider community.

While further mapping the wicked problem would undoubtedly raise more insights, the themes mentioned above will act as crucial nodes to design interventions for when remedying the wicked problem of isolation in older adults in Pittsburgh.

Assignment 2: Mapping Stakeholder Relations

Collaborators: Fas Lebbie | Tasha Russman | Serena Wang

Mapping Stakeholder Relations

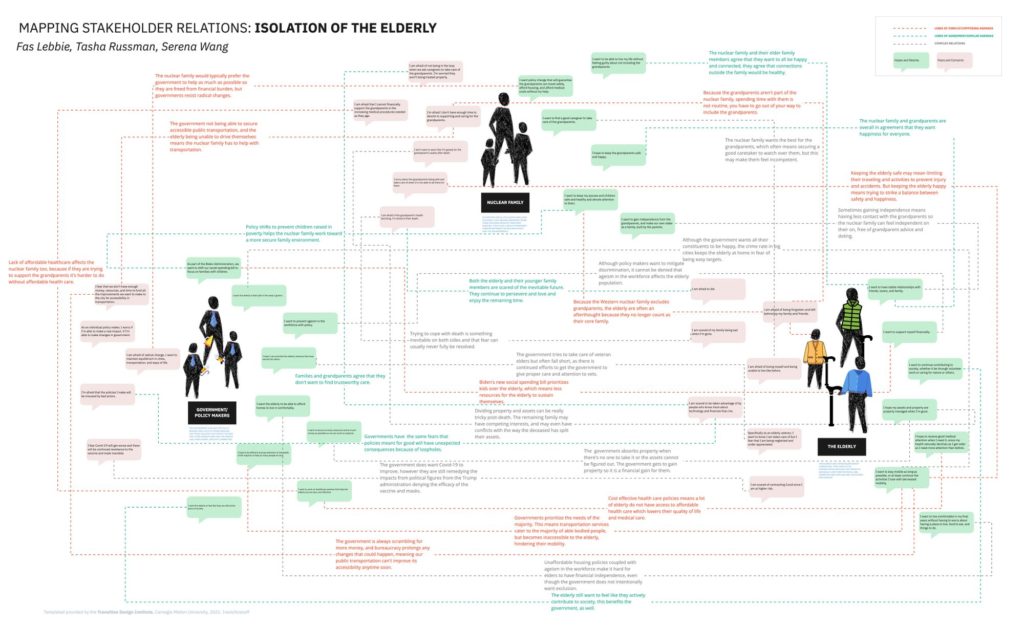

Understanding isolation of the elderly through the relationships that exist between the hopes and fears among the elderly, the nuclear family, and the government/policy makers.

Introduction

Isolation of the Elderly – Why it Matters

Older adults in Pittsburgh, PA, suffer heavily from the wicked problem of isolation, an issue characterized by its highly complex and pervasive nature. As older adults’ health declines, they simultaneously become increasingly isolated and lonely, contributing to further barriers to their overall wellbeing. For example, healthcare literature cites ample evidence linking loneliness to a higher risk of dementia and other severe health conditions. In Pittsburgh we see this, and other alarming trends in the midst of a $631-million budget shortfall that has left health and social care systems poorly equipped to provide the standards of care that the elders in our community need.

The isolation of older adults has been steadily growing within the context of the recent COVID-19 crisis. This, in turn, badly impacted Pittsburgh’s older residents who both died at a higher rate than expected and were more likely to become isolated because of care home visiting restrictions.

In mapping the wicked problem of isolation amongst older adults in Pittsburgh, we attempt to explore the complexities of this issue at depth, highlighting relationships between these factors and others, and shedding light on that which has caused and exacerbated them.

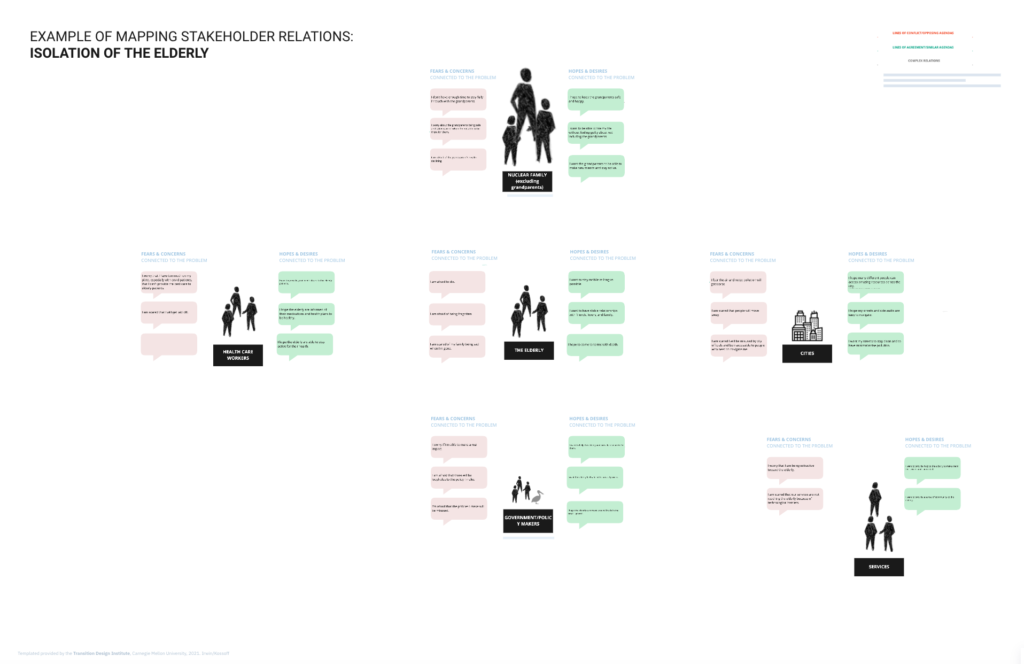

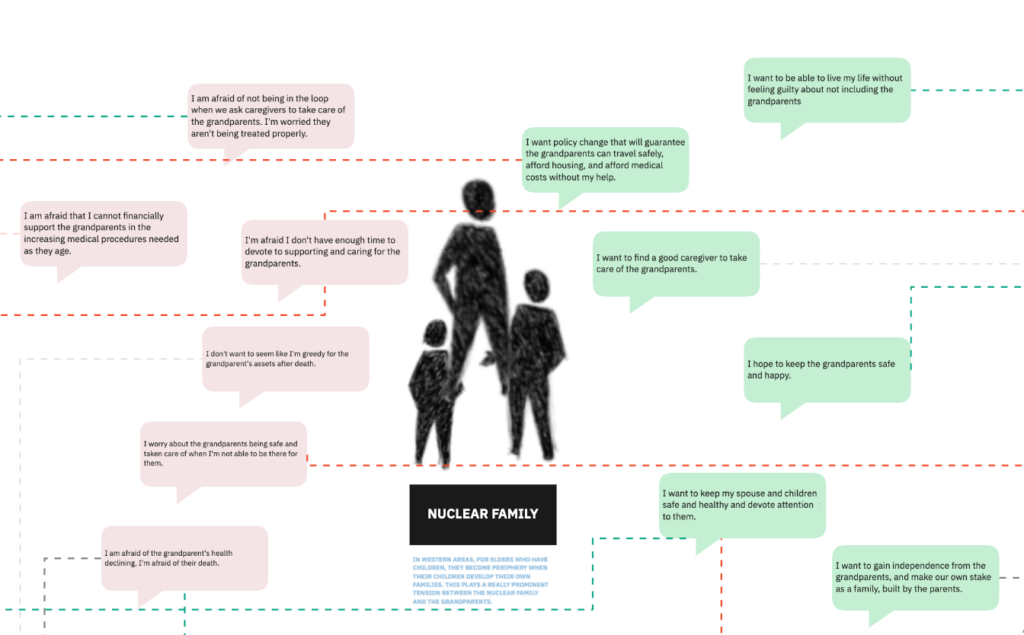

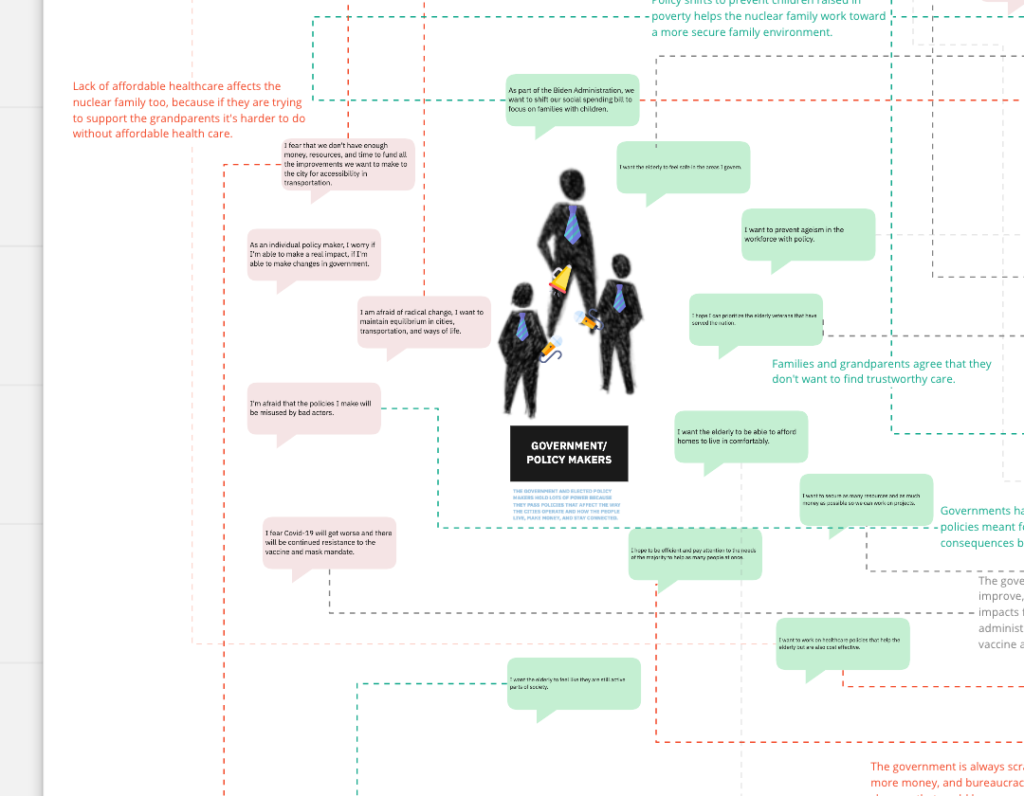

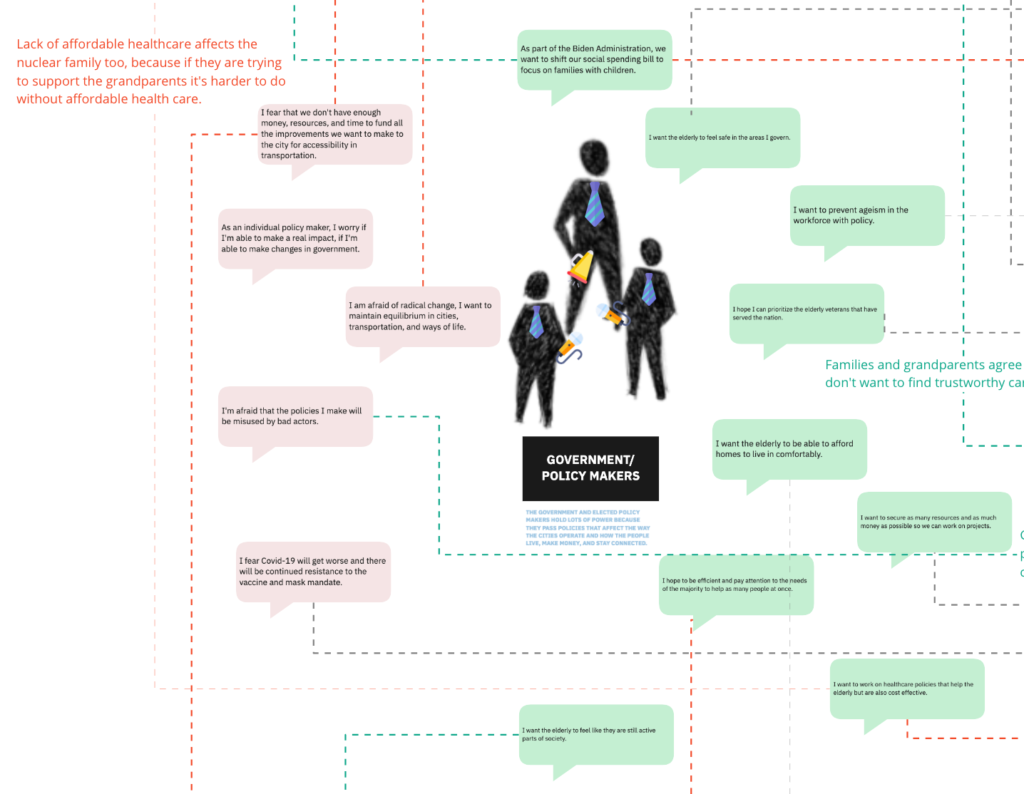

We identified three stakeholder groups to map out their relations to each other to understand the wicked problem further: The Elderly, The Nuclear Family, and The Government. A stakeholder is a human or non-human subject (individual or group) that is connected to the wicked problem, from being affected by it to exasperating it. We found that there were no “evil” actors, but rather a web of complex relations that were sometimes in conflict and sometimes in agreement.

Process

Initial Exploration: Stakeholders at Multiple Scales

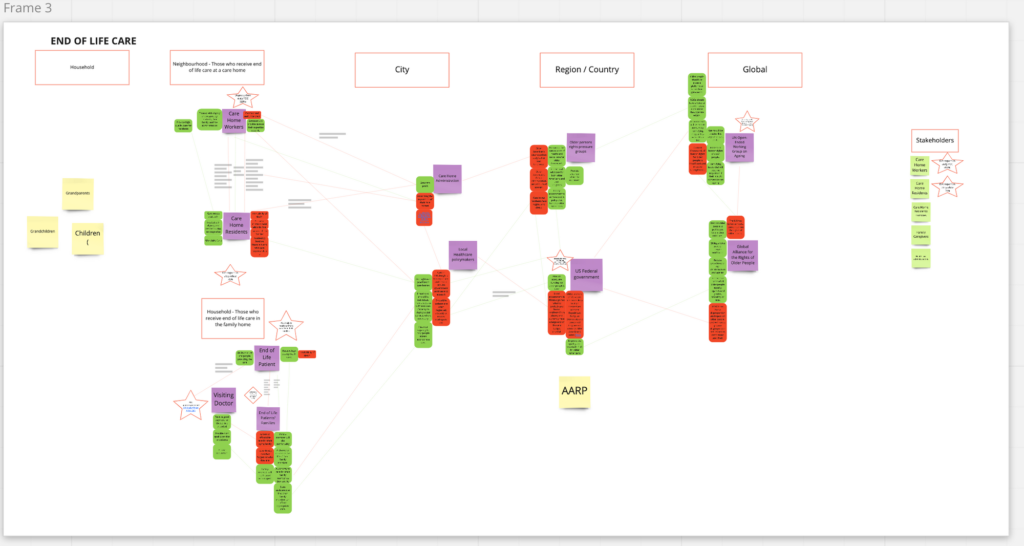

We began to brainstorm our stakeholders by considering which were relevant at various levels of scale. Each group member-generated stakeholders in isolation, and then we discussed our findings as a team. At the smallest, we had household stakeholders of the older adults. These included visiting doctors and the patient’s family. The next step was a neighborhood level that focused on local healthcare providers and older adults’ experience with them. Care home workers were one such example at this level. We then stepped up once again to the city of Pittsburgh, where we thought about administration and local government. The penultimate level was region and country, for which we situated older people’s rights pressure groups such as the AARP and the US Federal Government. Finally, we tackled the global level by selecting the “UN Open-Ended Working Group on Aging, and the Global Alliance for the Rights of Older People. We added additional detail by brainstorming the hopes and fears for each group and beginning to map where they come into conflict.

Following this process, we initially attempted to categorize our stakeholders into the three themes within isolation of older adults that we uncovered while mapping the wicked problem. They were end of life care, ageism, and lost identity. However, we ran into issues during this process. When we started with end of life care, we found the category becoming clouded, and as we moved onto the other two themes, we realized that there was overlap between all three themes. For example, healthcare workers could be situated in all of the themes. These difficulties forced us to rethink our stakeholder mapping process.

Grouping Stakeholders by General Categories

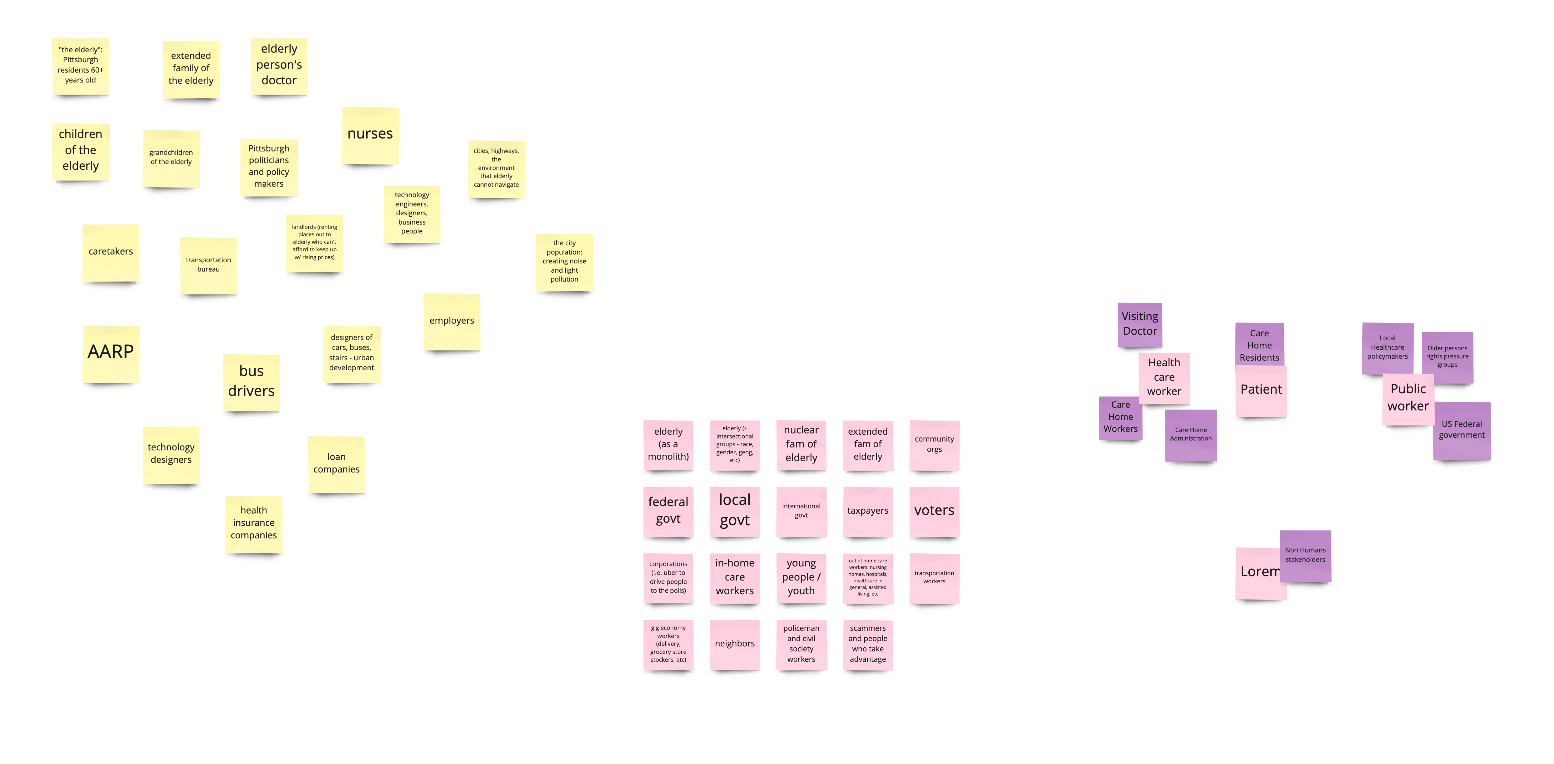

We realized we had come up with too many scales of stakeholders. Going into depth on mapping stakeholder relations would require us to reduce the number of stakeholders and scale up for consideration.

So, we took some time in a meeting to write down as many stakeholders we could think of that related to the theme (the themes were ageism, end of life care, and lost identity) we were responsible for in the wicked problem map. We found several theme based stakeholders overlapped.

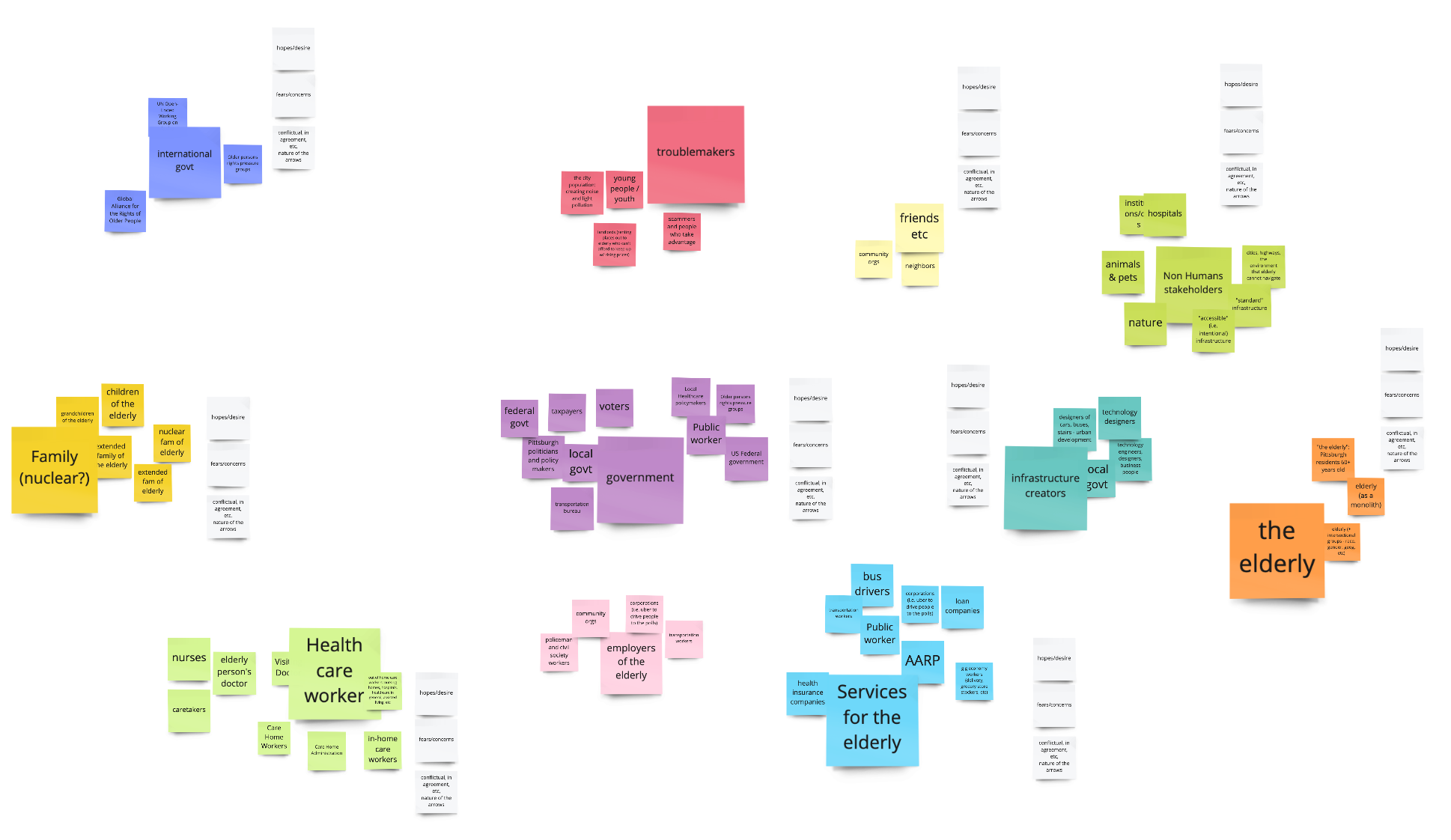

Our next step was to put the stakeholders into broader categories based on their similar jobs or relations pertaining to the elderly. The stakeholder buckets we created were: international government, nuclear family, government and infrastructure creators, services for the elderly, troublemakers, and non-human stakeholders.

Firstly, the international government encompasses the activist groups, organizations, and governing bodies that have influence on a global scale. Under the family (nuclear), friends, and healthcare workers buckets we positioned individuals with direct access to and connections with the older adult. Next, the government and infrastructure creators buckets referred to those who create the environment that older adults must exist within. Similarly, under the services for the elderly bucket we positioned the organizations that aim to help older adults navigate the built environment. Alternatively, the troublemakers bucket referred to the stakeholders who make it harder for elderly people to become active in their communities. Finally, non-human stakeholders featured the natural and built environments that older adults in Pittsburgh must navigate.

Scaling Down

And then for the final 3 stakeholders, we picked them based on who is in the most tension with one another due to the complexities of their hopes/desires and fears and concerns.

We decided to go with the nuclear family because their relationship is very different compared to extended family, friends, and community groups. When considering who holds the most complex relation, we decided nuclear families did because they have one of the closest relationships and dependencies to the related elderly. The nuclear family both wants to love and care for the elderly family members, but at the same time have their own space to live freely. Grandparents were once part of the nuclear family with their children, but having a new relationship with their children where they are no longer part of the nuclear family creates a liminal identity where grandparents aren’t sure where they exist in the family dynamics anymore.

The elderly themselves are a stakeholder and the most important because all the relationships that exist in this wicked problem center around this group. Sadly, the elderly are also the group with the least amount of power. As elders naturally age, they lose cognitive and physical abilities which hinder their autonomy and power.

We took an optimistic stance on government/policy makers, giving them the benefit of doubt that they do in fact want the elderly to be safe, happy, and fulfilled in life. The main concerns the government has surround the feasibility to exact change

Content

Analysis of Relations

A review of relations between The Elderly, The Nuclear Family, and The Government in Pittsburgh surfaced conflicting relationships at different levels of depth. On the surface, all three groups signal interest in the well-being of the region’s elderly. However, a deeper look at the incentives structures below the surface tell a different story, better described as interest in the basic survival of the elderly, as opposed to creating systems designed to help them thrive.

Government <> Elderly

It should be noted that, at their core, all three groups are ultimately made up of everyday people most of whom come from some kind of family, whatever form that may take. As a society and as individuals, for the most part we love our parents and grandparents, we wish the best for our neighbors, and we appreciate the loyalty and continuity that they bring to our lives, our communities, and our constituencies. At both a personal and governmental level they serve as the matriarchs and patriarchs that hold values steadfast even as the world continues to change.

This root that causes friction between vocalized desires and institutional behavior can be attributed to chronological realities of the human lifespan as compared to governmental and systematic bureaucracies. Older adults have just a few decades between when they begin to transition to a more “elderly” way of life and when they pass on. Meanwhile, governmental change is slow, with years passing between legislation getting proposed, passed, and implemented. It’s very possible that a piece of legislation could be proposed with the elderly in mind without getting passed or implemented within the remaining lifespan of those individuals.

Turning to one of the most common forms of governmental support for the elderly, we see that social support systems like Medicaid and Medicare suffer the same issue at a much greater scale. While today’s elders paid taxes throughout their lives to contribute to those who came before them, they are now dependent on today’s taxpayers for their own support. This system has introduced a crisis in which top-heavy age demographics leave a disproportionately large group of seniors dependent on the funds of a much smaller group of taxpayers. This is just one example of a system that may appear to support our seniors without actually doing so to a suitable degree. Other areas where we see government directly fall short include protections against ageism in the workplace, guaranteeing affordable housing and healthcare, providing accessible basic infrastructure such as transportation and technology, and providing opportunities for social support in the community. These issues were all measurably magnified the past two years in light of COVID-19. Finally, while outside the scope of this write-up, it is worth mentioning that one of the deepest fractures between incentives of the government and the elderly occurs when someone dies. Together, estate taxes and property acquisitions make up one of the largest sources of wealth distribution in the country, creating diverse perverse incentives between the health of the government and that of an individual.

Government <> Family <> Elderly

The elderly and their families also offer an initially sunny picture: they love each other, want the best for each other, and are willing to work together to do the best they can. But, here too we see more complexity among the complex dynamics that flow below the surface. We must first look to the same “chronological reality” mentioned above – that is, by nature, the elderly 1) are significantly further along in life than their younger counterparts and 2) generally have fewer years of “productive growth” and opportunity to influence the economy and society than do their younger counterparts.

Our analysis showed little evidence of the government prioritizing support to the elderly, instead focusing on areas associated with more opportunity for “a better future.” The Biden Administration’s latest infrastructure plan, for example, prioritizes young children over older adults. Again we see something that, in theory, everyone can get behind. The problem is that by not providing support directly to the elderly, the government just pushes the problem downstream, where it draws from other budgets and creates negative consequences for other stakeholders.

In one case we have an elder who lives with the support of her children because she can’t make ends meet. When government assistance is allocated to early childhood education instead of healthcare for the elderly, her family ends up footing the bill for her medications. On the one hand, they are grateful to have saved money on the young one’s education. On the other hand, they don’t ultimately benefit from this saving because they’ve now spent it on their mother instead. Even more counterintuitive is the case of the elder who doesn’t have family to turn to for help. In this case, taxpayers ultimately foot the bill because he still gets sick and ends up in the hospital, where someone needs to pay the bill. Worse yet, the bill is likely to be higher if he’s put off the visit for lack of funds.

Returning to the idea that ultimately the elderly and their children generally share compatible goals around loving and supporting one another (characterized as an “affinity” relationship), we can now see where downstream consequences from insubstantial government support can start to complicate things. In short, the family is now put in the position of acting as a conduit of funding for the elders. Indeed, this is more than just semantics – already at risk of being stripped of community, self-worth, and independence, the elder is now put in the position of “burdening” their family by adding costs to their budget. Through the lens of this analysis it may be easy to point to the upstream decisions responsible for this financial breakdown. However, by forcing the money to go through the family, the system inadvertently filters it through the already complex familial relationships. This is just one example of such a phenomenon, but a quick look at failures in infrastructure, accessible transportation, etc surface the same pattern.

Conclusion

In short, our stakeholder analysis shows varying levels of complexity of relationships. Initially it’s easy to walk away with the satisfaction that everyone wants the elderly to be happy and healthy. However, a second look reveals that for funding to ultimately cover the basic needs of our older Pittsburgh residents, it is often forced to filter through family first, opening up second- and third-order consequences in private life that is often already fraught with complexities and dynamics. When push comes to shove, an individual will often get the basics they need to survive. But the more barriers and complexities we introduce along the way create worse outcomes for everyone.

Bibliography

- “Age Discrimination: 25 Crucial Statistics.” SeniorLiving.org, Seniorliving.org, 17 Feb. 2022, https://www.seniorliving.org/research/age-discrimination-statistics-facts/.

- Brooks, David. “The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake.” The Atlantic, The Atlantic, Mar. 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2020/03/the-nuclear-family-was-a-mistake/605536/ .

- “Impact of Age Discrimination – AARP.” The Economic Impact of Age Discrimination, The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2020, https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/surveys_statistics/econ/2020/impact-of-age-discrimination.doi.10.26419-2Fint.00042.003.pdf.

- Markwood, Sandy. “What Policymakers Must Know about an Aging America – N4A.” Edited by Amy E Gotwals and Autumn Campbell, National Association of Area Agencies on Aging Policy Brief, e National Association of Area Agencies, Jan. 2017, https://www.usaging.org/Files/n4a_PolicyBrief_WhatPolicymakersMustKnow_Jan2017_final.pdf.

- News, Bloomberg. “After Decades of Focus on Elderly, Washington Turns to Families – BNN Bloomberg.” BNN, Bloomberg, 5 Nov. 2021, https://ampvideo.bnnbloomberg.ca/after-decades-of-focus-on-elderly-washington-turns-to-families-1.1677415.

Assignment 3: Mapping the Evolution of Isolation among Pittsburgh’s Elderly

Collaborators: Fas Lebbie | Tasha Russman | Serena Wang

Mapping the Evolution of Isolation among Pittsburgh’s Elderly

Understanding isolation of the elderly through a multi-level perspective across time

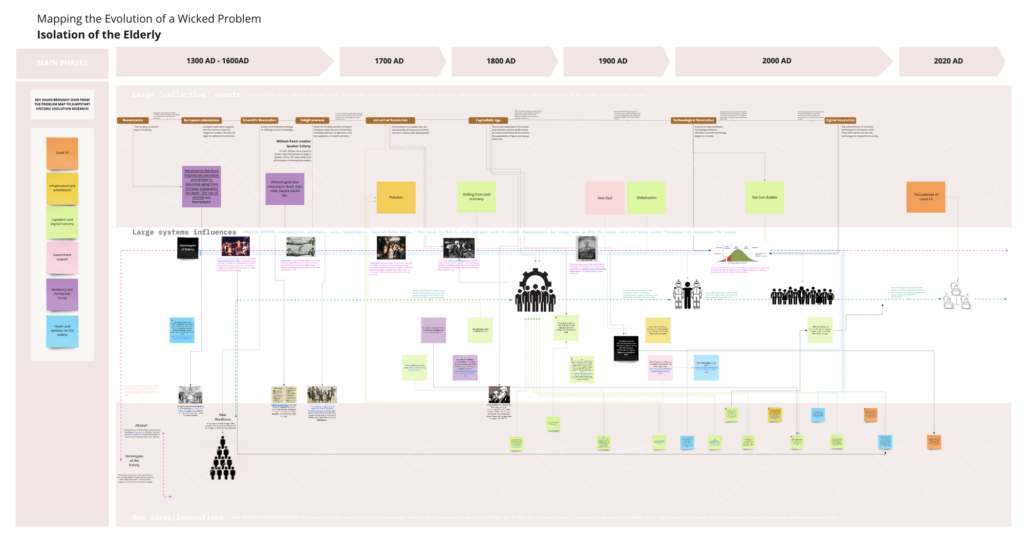

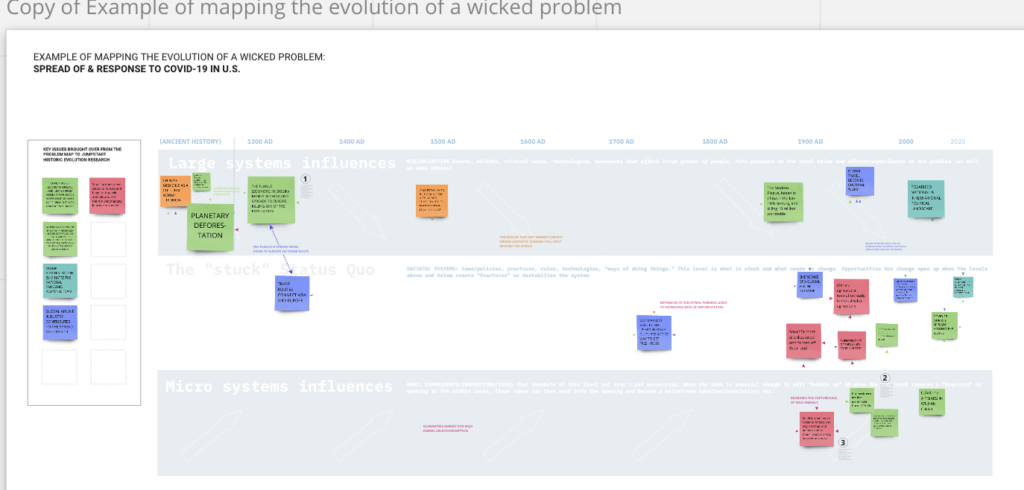

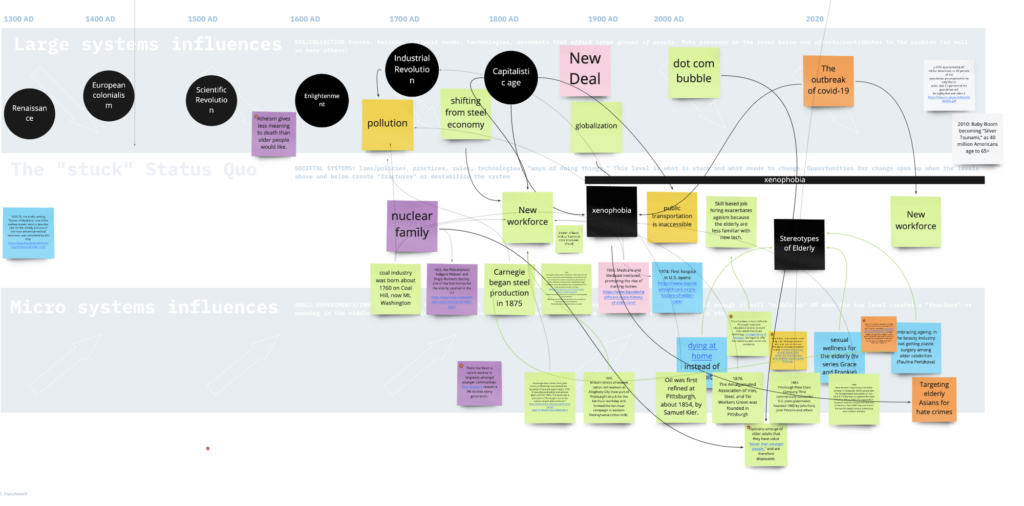

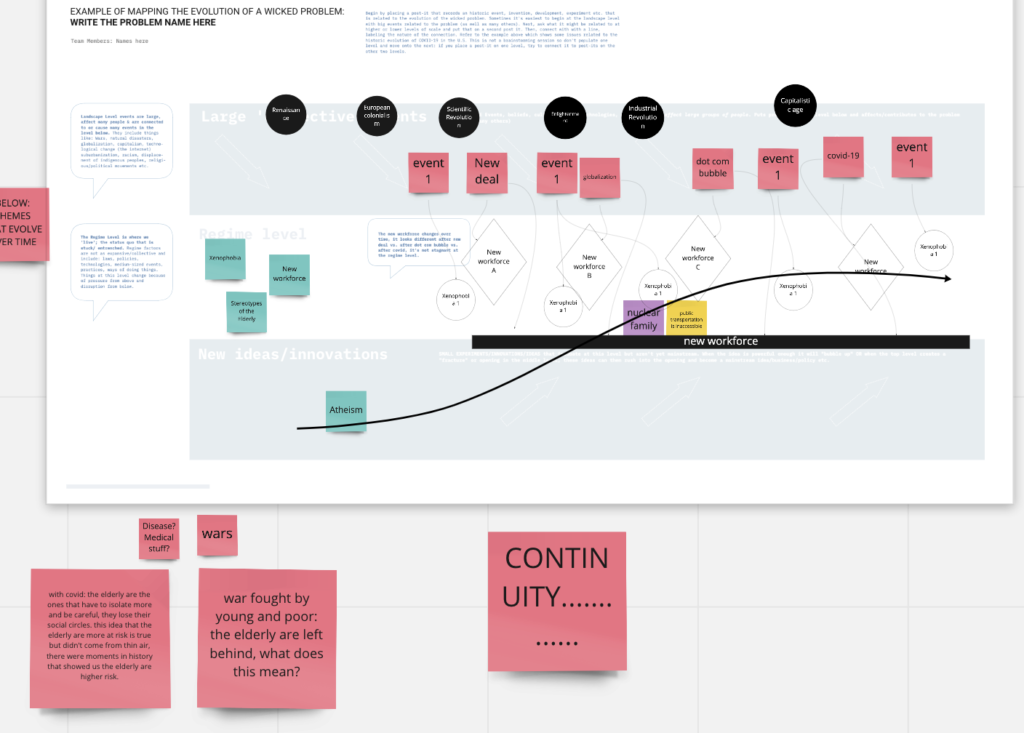

Introduction

In previous posts we explored the wicked problem that is isolation among Pittsburgh’s elderly through a LANDSCAPE MAP and STAKEHOLDER ANALYSIS. However, underlying both of these analyses of the present landscape, it’s important to pause to reflect on how we got to where we are today. We focused on historical events that gave rise to the trends (and their evolution through time) that eventually led to our situation at present. To do this, we employed the multi-level perspective framework, through which we mapped events between several socio technical levels: the landscape (i.e. macro-level), the regime (i.e. meso-level) and the niche (i.e. micro-level). In doing so, we situate contributing factors within the greater context of what society looked like, both then and now.

To fully appreciate the factors that led us to our current state, we must first briefly review how transitions and societal change come to pass. To understand this, we draw from Geels’s work in 2005, which highlights societal transitions as changes that occur a) at multiple levels and b) across varying patterns of rhythm and time. Historically, techno-sociologists have long alluded to the many layers of complexity in patterns of change, as well as the idea that the change itself occurs not in artifacts or events themselves, but in the relationships and spaces in between them. Through this lens, we can imagine a timeline as we would a sheet of music; while theoretically it is possible to have many single notes exist in isolation, it is the connections between the notes that combine to create a musical piece itself. Geels takes this one step further, adding what we would compare to the staccato and legato rhythms that characterize those notes and their relationships with one another.

As mentioned above, the MLP framework differentiates three main levels of interplay between factors and relationships. First, we have the Landscape Level, where we see the largest, slowest-moving events, generally characterized by their inertia or accrual over time. At the meso level, we see the Regime, best defined as the “status quo”. Finally, the micro, or Niche level is home to the grassroots. Together, according to Geel, the interplay between these three levels each with their own rhythm and timing, form the evolution of the complex systems we see in present day. This level of nuance fits our historical perspective perfectly; it allows us to chart the most salient elements that rise to the surface over time, and to do so without confounding timing or size for value or influence on present day context.

Process

1. Initial Exploration: What and When

The first question for us to address was how far back in time would be relevant for the team to research. Our map would take the form of a timeline of sorts, so it was important to strike a balance between space constraints and ensuring that we included the most relevant parts of history, however far back they fell.

1.1 What Themes Should We Focus on?

We took advantage of our varied group members, each of us independently evaluating our former maps and surfacing several themes that we found most prominent, and coming back together to compare our findings. There were several themes that immediately stood out as popular: COVID-19, technology/digital economy, and infrastructure/urbanization. We adjudicated the rest, separating the other most salient patterns (i.e. modernity/nuclear family structure, and atheism/religious belief) from the rest.

1.2 How Should We Represent Relevant Epochs in History?

The next stage was to take the themes we had identified, and trace them back in history to their most significant antecedents. Ironically, this process was more organic than it was linear. First, we found that charting our first set of data left us with significant chronological outliers; for example, we see the first evidence of senior care among human remains from 500,000 BCE. Certainly elder care is a very important thread in many aspects of isolation of the elderly; but, without any other relevant or related events to point directly to that event or others over the next few epochs, we ultimately decided to drop this node, and other similar ones from our timeline.

After settling on a timeline that would present a suitable canvas to represent the evolution of the problem, we moved onto the next step: how to represent that timeline: should we chart specific years? Decades? What intervals should we use to space out the narrative? How else might we represent time periods in a way that communicates the “when” in such a way that it scaffolds our narrative?

Several iterations later, we landed on organizing our timeline through chronological time periods. This decision was an important one because it represented a move from a more quantitative communication style to a more qualitative one, or a prioritization of holistic/organic > linear. That is, to best situate the evolution of our problem, we wanted to communicate the overall societal and cultural context at that time, as opposed to a more exact measure of “when” or “how long” certain points of a transition might take. Ultimately, the earliest starting point that made sense to kick off our narrative was the Renaissance, which represents a time when, around the world, our elders were held in high esteem for their wisdom and accumulated life experience. Below is a list of all time periods we included:

- Renaissance

- European Colonialism

- Scientific Revolution

- Enlightenment

- Industrial Revolution

- Capitalistic Age

- Technological Revolution

- Digital Revolution

We tested several iterations of this model and ultimately included a high-level timeline outside the main map as a reference point for viewers.

1.3 What are the Narrative’s most Salient Themes?

With the tentative boundaries our timeline established, we populated our map with several prominent events, and set about building the web around them, asking ourselves, “what caused this event?” And, “what else did this play a major role in causing, in turn?”

As with our first research phase, this one, too, was anything but linear. The three of us jumped all over our timeline populating it with contributors to themes we had pulled in our previous analyses: xenophobia, the new workforce, stereotypes of the elderly, and atheism. At this initial stage, our goal was to simply get ideas on the board; our contributions ran the gamut, falling at all levels of abstraction. We threw on sea changes such as The Beginning of the Steel Age and The Dot Com Bubble, and specifics such as a Coverup of a Covid Outbreak in a Nursing Home. There were arrows flying everywhere, looking like a soft of controlled chaos, and displaying the underlying complexities of some of these issues.

We asked questions such as, “can a Niche event both cause, and be caused by, a regime-level relationship?” We grappled as a team to understand the difference between coincidences and cause-and-effect, or roots of a mutual transition as opposed to distinct phenomena. Though time-consuming and at times, frustrating, this process was invaluable because through it, we were forced to confront assumptions we had made about how consequential certain themes might be. More specifically, despite ample pulling and prodding, this process clarified that Xenophobia was not nearly as influential as we had initially hypothesized. In our final steps of this stage, as some themes solidified others did not, clarifying where we could consolidate or trim our fat to better accentuate the main contributors to the narrative: Atheism, the New Workforce, and Stereotypes of the Elderly.

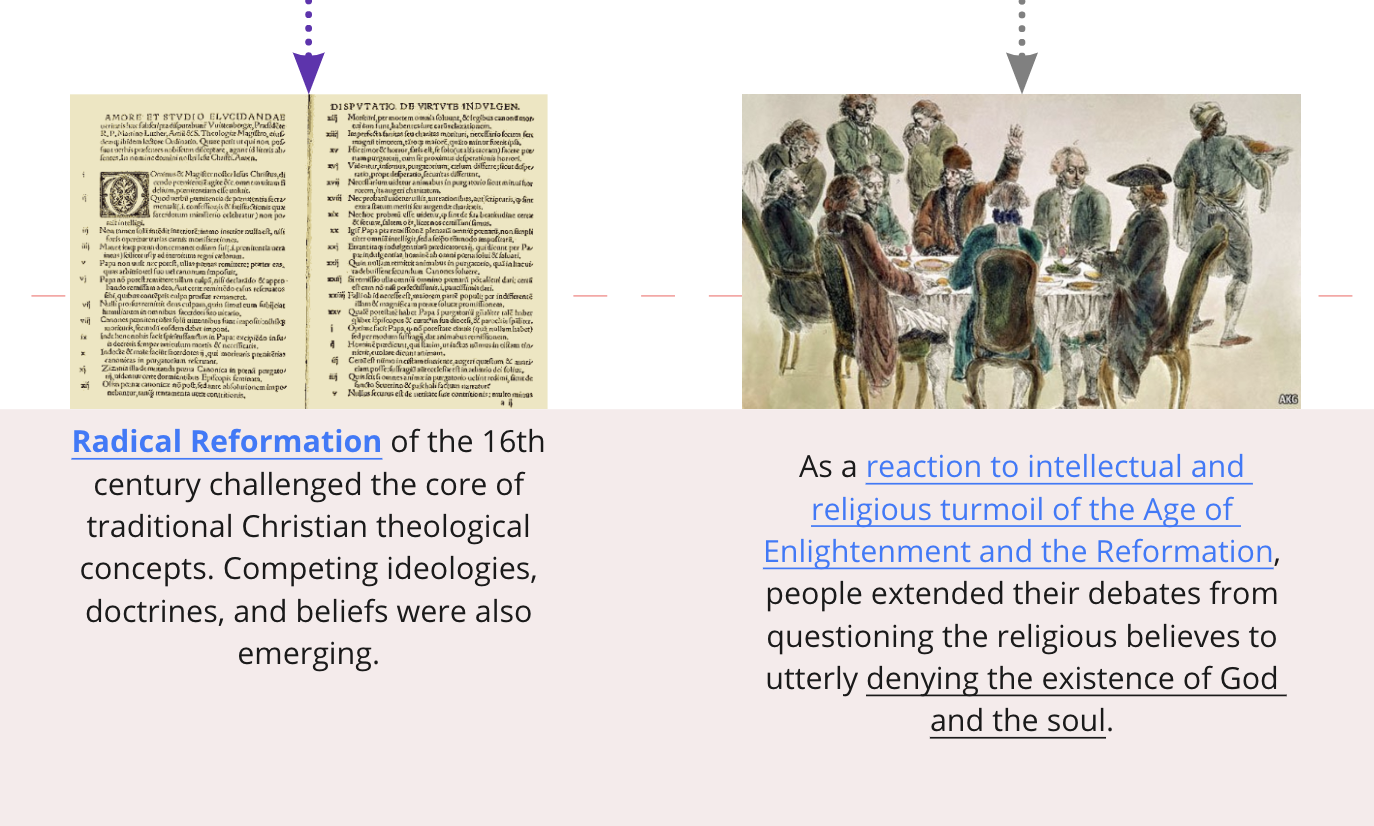

Theme 1: Atheism

Our timeline begins around 1300 AD, in the age of the Renaissance. This era, characterized by individuals beginning to question the church, is relevant to the isolation of the elderly in Pittsburgh because of the implications it has on religiosity more generally and by extension, the meaning we attribute to life and death.

We see this line of thought evolve from the Niche level (i.e. individual scientists getting executed for their work) to the Regime (i.e. status quo) closer to the 1900s. We see this trend mirror a growing gap between the nuclear family (and local community) and their elders; what was once considered an accumulation of wisdom and wealth (at least of love and life experience) slowly shows less and less value over time, as evidenced by the elderly in communities being regarded as peripheral as opposed to core, or burdensome as opposed to sacred. We see this through institutions and literature that group the elderly with the sick and frail, removing them from the fabric of society and thus planting the seeds of isolation for generations to come.

Jumping to the present, Pew research cites a 9% decrease in religiosity with every generation. But, without new structures or institutions to connect our elderly through community as religious institutions once did, the cycle of isolation persists.

Theme 2: New Workforce

The New Workforce is a term we use to distinguish from The Old Workforce, as opposed to any one specific moment in time. It speaks to a tension that has been present through the ages as technologies are introduced to society (and are therefore considered new), which in turn threatens to turn “current” (at any given time) status quos into relics that will soon be considered old as society continues to evolve. Thus, when mapped onto our MLP Framework, the overall theme sits at the Regime level, while inherently relying on continuous inputs from the Niche.

Our narrative around this phenomenon in Pittsburgh begins in the time of the Scientific Revolution, which is where we see the roots of manufacturing. This is relevant because, while able-bodied-ness was always strongly valued, this was the era in which collective systems began to use this as a basis to discriminate in a much more formalized way. Here in Pittsburgh, this ties closely with the evolution of the glass and steel industries, in essence setting precedent for the entire country (then dependent on both of these industries to fuel the country’s rapid industrialization) to value an individual based on the extent to which they were/n’t able to contribute to their local economies.

Fast-forwarding to the past decade or two, we see the same trend continue, albeit having replaced brute strength with access and skills in white-collar work and technology. There is much to say on this topic that is outside the scope of this paper (please see our earlier analyses for more detail); for now, we will focus on two overt contradictions between this idea of the New Workforce and the space it (fails to) create for aging populations, significantly magnifying their isolation in society.

First, in our current digital age, we see the continuation of the earlier theme of able-bodiedness take on a new title, accessibility. While it may on the surface appear softer, lack of access to valuable software content, UI, and skills, is just as insidious as the inability to work via the manual labor of Pittsburgh’s roots. As long as we consider the “norm” to be a young, able-bodied person, we are inherently setting up a society in which every single person will, if they are so lucky as to live long enough, be considered “disabled”. Indeed, the norm for both software and hardware developers is to cater to this able-bodied population, leaving anyone with differing physical or cognitive abilities, or even life experience, to find their own way. In the context of the New Workforce, this is nothing short of structural discrimination against any elderly individual who experiences such common symptoms of old age including arthritis, tremors, decreased vision, decreased hearing, etc.

Second, the presence of the digital age brings with it a renewed belief that “you can’t teach old dogs new tricks.” That is to say, the individuals and systems that influence, and are influenced by, the technology described above assume that the elderly are incompatible with most technology. We see this in a lack of technological training for the elderly, as well as systemic ageism across the workplace (including the talent acquisition that serves as gatekeeper to enter the workforce in the first place). In a context like Pittsburgh’s, in which manual labor is quite literally being replaced by high-tech jobs, one need not look far to see our elders systemically excluded from opportunities in industry, society, and organized community.

Theme 3: Stereotypes of the Elderly

As we see above, the technological and digital revolutions provide a significant uptick in stereotypes among the elderly. Building on the stereotypes that the elderly won’t be able to use technology, we also see evidence of stereotypes that they are considered laggards, preferring to stick to outdated technology long after it’s obsolete. However, we should also note that recent needs precipitated by the COVID pandemic social restrictions proves ample evidence to make society question the soundness of this claim. But, the reality is that despite the availability of such evidence, we see society continue to stick to this unfortunate narrative.

Stereotypes developing through time:

- 1500s: royalty want to be portrayed as young, stereotype of youth and wealth being correlated

- 1600s: medical care is seen to be palliative for issues related to aging, reinforcing a stereotype that the elderly are beyond help

- 1700s: more positive stereotypes of the elderly being wise

- 1800s: industrialization means you need more physical health to get money and jobs, so aging was seen as a big disadvantage to living

- 1900s: fear that living longer for elderly meant putting strain on the youth population. Social security created to help the elderly

- 2000s: digital revolution, eldery seen as “laggards”

In addition to attitudinal stereotypes, Pittsburgh’s elderly must also weather bodily stereotypes. Again, as mentioned earlier, we see this trend begin back in the 1400s in London, when the elderly were first housed with the weak, frail, and mentally ill. We see this attitude continue through the context of able-bodiedness in the workforce, and finally we see it come to a head in the wake of COVID-19, when we literally cordoned off physical and chronological spaces to keep our elderly separate from the rest of society, lest they “succumb” to the illness. In such circumstances, it is easy to forget that our elderly aren’t a monolith, and that just as we all have stories of friends or family who have suffered from covid, many of us also have stories of the countless grandparents who hardly felt sick at all.

Note: After receiving feedback on our map, we added a few modifications to further clarify several of the connections between relevant nodes. Specifically, several nodes were not visually connected to others, nor did they have explanatory text explaining those connecting lines. All qualitative content remains the same.

Assignment 4: Designing for Transitions

Collaborators: Fas Lebbie | Tasha Russman | Serena Wang

Introduction

For Assignment 4, Team Resilience was asked to consider the problem space that we had previously investigated around Isolation of the Elderly in Pittsburgh and begin to design a long-term vision of a future where this problem had been mitigated and rectified. We did this through two steps: (1) developing the future and (2) backcasting & assessing the present.

In working through this assignment, we carried over the main threads that we had unearthed while mapping the evolution of the wicked problem: (1) a job market that discriminates against older Americans’ skills, (2) a technological revolution that has left them behind rather than supporting them, and (3) environments that are minimally accessible for members of society outside the cultural norm.

Step 1: Develop the Future

Process

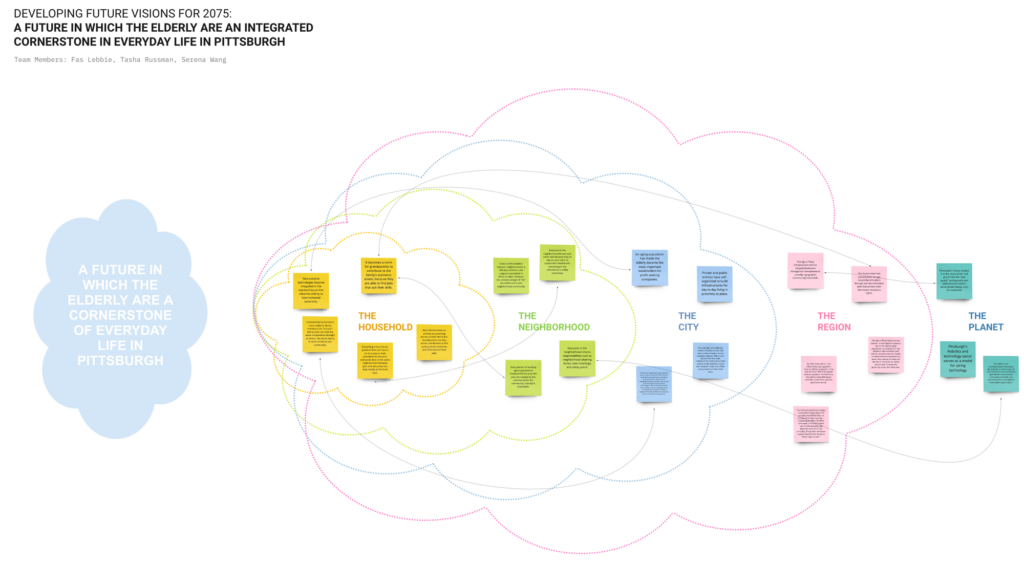

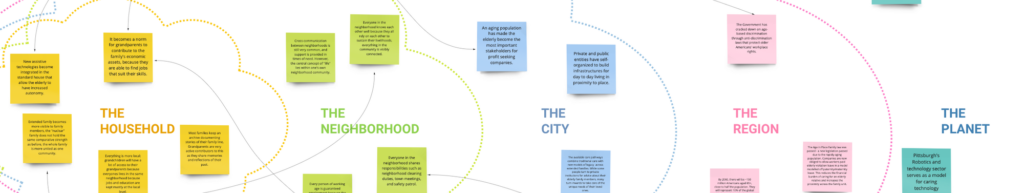

Our objective for developing the future was to do so with the ideal in mind, and without regard to the current state of affairs, or what may be considered more/less realistic. We developed a vision of a Future in which the Elderly is an Integrated Cornerstone in Everyday Life in Pittsburgh. This vision was driven by the idea that an equitable future would be one based on connection and belongingness, and that to keep the model sustainable, it must be fully integrated into the systems of the rest of society. It should be noted that our vision was highly informed by several themes we had recently discussed in class: Cosmopolitan localism, Commoning & Mutual aid, and Manfred Max-Neef’s Theory of Needs.

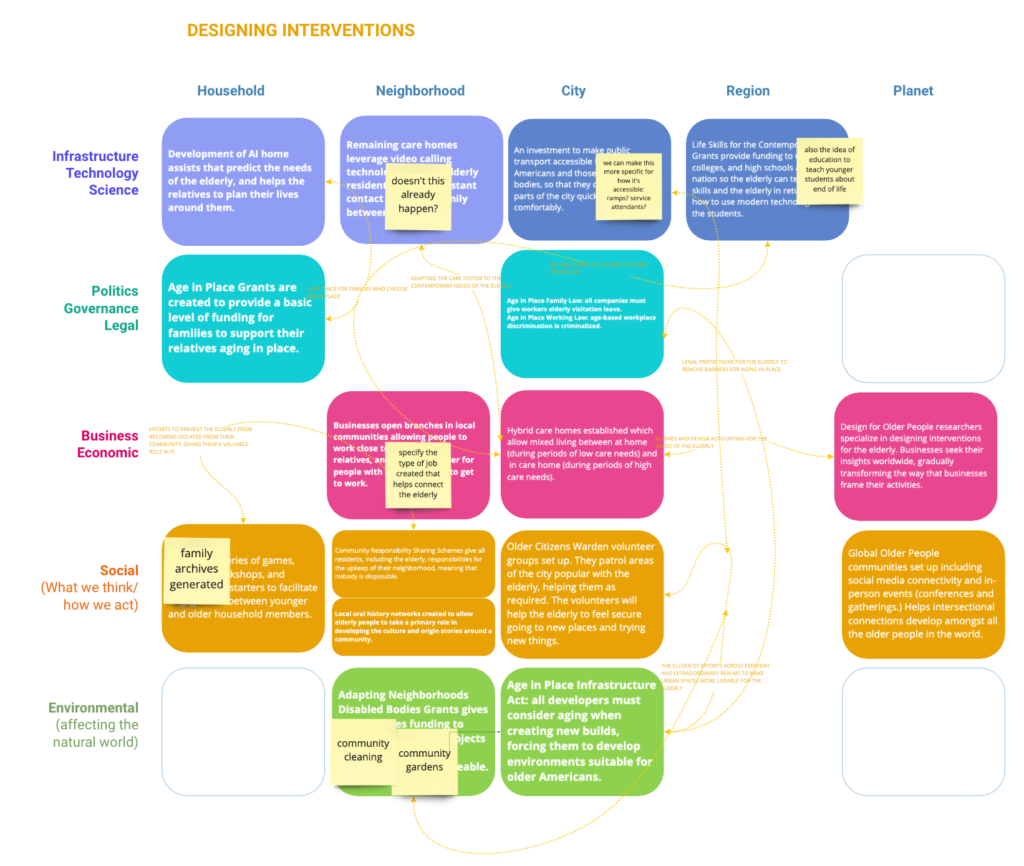

We worked from a futuring framework based on Kosoff’s idea of the facets of everyday life that are divided by levels of scale: the household, neighborhood, city, region, and planet.

The team started by distributing one or two sections to each member to kick off some initial ideation; this allowed us to start several separate threads at once, independently of each other. This was important because we needed a mechanism to solve for both breadth and depth (i.e. relationships across levels) – this was the basis of achieving our desired breadth.

With several initial ideas mapped across levels, we then came back together to review each as a team. Through review and adjudication, we honed our ideas and edited our map. We had two main takeaways from the process; first, it was surprisingly difficult to break free of our but is it realistic mindset. Even with the explicit goal of ideating around an almost unreasonably ideal future, all three team members defaulted to probable AND ideal futures, as opposed to just ideal ones. Throughout the process, we regularly had to reset our frame away from the probable, logical, and sensible and in lieu of the desired, sustainable, and equitable. We similarly defaulted toward narratives and away from scenarios. This reflection is testament to the value of this process: if a team of designers with the explicit goal of changing their dominant mindset has such difficulty doing so, even for a short time, it’s no wonder that evolving a group’s or society’s mindset is such a tall order.

The second takeaway our process highlighted was that themes across levels seemed fairly clear; that is, after accounting for the trimming we did due to mindset (as described above), the majority of the ideas we had generated separately (and across levels) were already significantly related to one another. As such, the majority of our work was to tweak those ideas to better support one another, as opposed to completely deleting many or ideating anew. One example of such a theme is care work, which shows up at the Household level as the nuclear family, at the Neighborhood level as neighbors and community members, at the City level as a combination of the two, and at the Regional and Global levels as legislative and tech issues, respectively. This phenomenon could be attributed to either the researchers (who have all been working closely with the same material for some time now), the previous themes that had been salient in earlier project phases, or the nature of the content itself. Unfortunately, investigating this question is outside the scope of the current work.

Finally, having completed a satisfactory map, we developed a narrative around what that future could look like, and how the many smaller pieces from the sticky notes could fit together to complete the puzzle that was our vision of a Future in which the Elderly is an Integrated Cornerstone in Everyday Life in Pittsburgh. We invite you to explore the map elements and narrative further below.

Map Content

As mentioned above, we considered what our long-term milestones would look like in further detail according to Gideon Kossoff’s five levels of scale within the domains of everyday life. Below we introduce the content developed in greater detail.

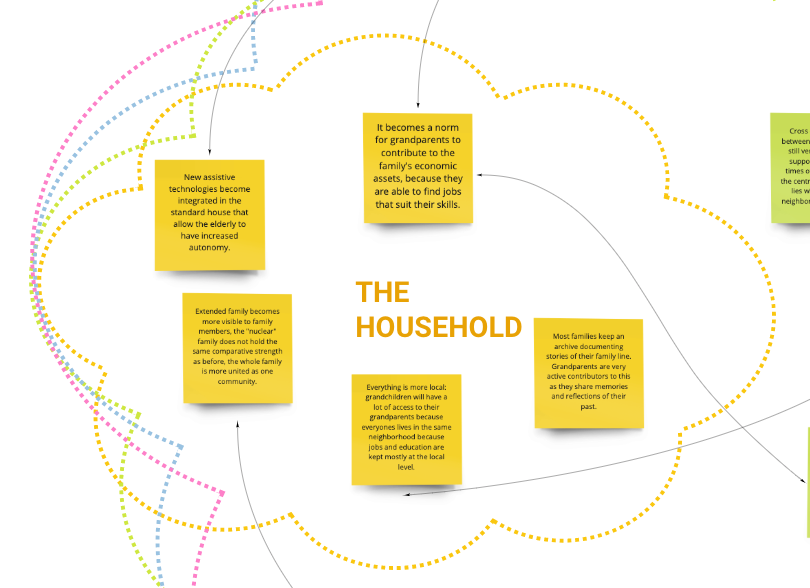

The Household Level

In the “Household” domain of everyday life, Serena imagined a future where the elderly can use their skills to actively contribute to a family’s economic assets by entering the workplace and using their wages to elevate the living standard of the whole family. The elderly would also be culturally significant amongst the family, becoming a kind of oral historian who shares their memories and reflections within the household. These interactions would be made possible by the denuclearization of the family, fostering especially close connections between grandchildren and grandparents.

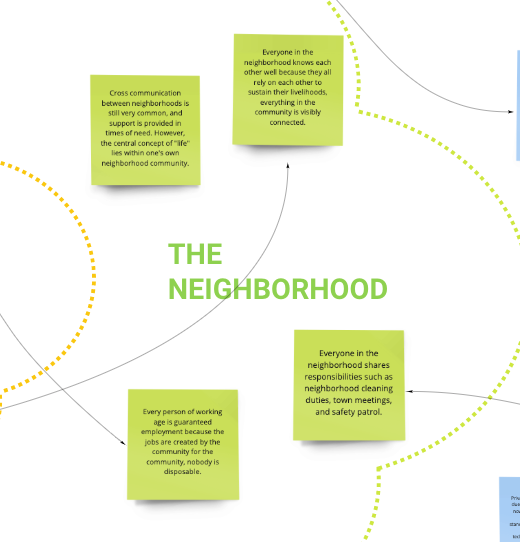

The Neighborhood Level

Serena then stepped up a level, considering how the “Neighborhood” could be firmly interconnected to improve the standard of living for elderly people. Sharing responsibilities would ensure that everybody knows and is looking out for vulnerable older citizens who are given purpose through jobs created by the community and for the community. These opportunities would allow the elderly to remain active participants who provide tangible value to their communities.

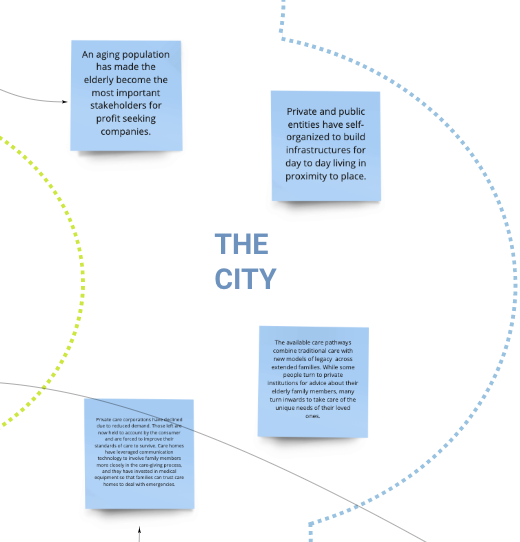

The City Level

The “City” level was when Fas stepped in and considered how care pathways would have changed in the future. As previously mentioned, reduced demand for care homes would lead to many of them collapsing. This would foster a hybrid system for caregiving whereby most older adults receive care at home, facilitated by active and high-quality assistance from professional care workers. Secondly, Fas considered how population changes would lead to the elderly becoming considered valued stakeholders. This change may force development companies to ensure that their infrastructure allows older people to remain in proximity to their homes.

The Regional Level

Fas also considered “Region,” looking into the impact of these demographic changes on a larger scale, asking how older Americans representing almost half the U.S population would change the political workings of American society? Fas designed three pieces of legislation that a future society would need to fit the needs of this new population group:

- An Age in Place Infrastructure Act would force developers to consider aging in new builds so that the elderly are not exiled from their homes as the surrounding environment becomes less accessible.

- Anti-discrimination laws would crack down on age-based discrimination in the workplace, ensuring that elderly people do not lose access.

- Age in Place Family Law would provide support to the family of the aging, obliging businesses to give workers paid leave to support elderly relatives.

The Global Level

The final level of scale is “The Planet” which Tasha covered. Tasha aimed to tackle connections between the local and the global and the role of technology on a worldwide scale. She asked how Pittsburgh’s envisioned aging processes could impact the whole of Earth? Firstly, Tasha looked at technology, considering how further growth in Pittsburgh’s robotics and technology sector would allow the city to develop caring technology that improves the lives of elderly people worldwide. Secondly, she looked at Cosmopolitan Localism and how it could decrease older Americans’ dependency on external goods and services. Therefore, they would be able to easily obtain Max-Neef’s tangible needs in situ while leveraging global connectivity to realize their non-tangible needs.

The Narrative to Accompany the Map

THE VISION OF A FUTURE IN WHICH THE ELDERLY ARE AN INTEGRATED CORNERSTONE IN EVERYDAY LIFE IN PITTSBURGH

There is strength in numbers, as evidenced by the comprehensive services and integration by, and for, Pittsburgh’s elderly in 2080. With nearly half the population aged 65+, we see that families, neighborhoods, and communities have adapted to serve the needs of a more holistic, integrated lifestyle that favors our elders. Driven primarily by demographics, capitalism has adapted itself to fit the needs of the day, compounding momentum behind elders’ values, needs, and strengths alike.

At a market level, we see the demographic change incentivize companies and governments to put elders’ first, to be able to capitalize on their power as both consumers and producers. As consumers, The elderly hold enormous spending power; having always been an outsized demographic group, they are now living longer, and with an improved quality of life that allows them more autonomy to control, and enjoy their own livelihoods much longer than previously possible.

This new spending power gives them first priority in the eyes of consumer-facing businesses, who now dedicate vast resources toward better understanding, testing, and developing technology that can drive adoption from this previously ignored user group. Set at the center of technological development in this space, Pittsburgh’s inclusion of their elderly sets an example for the rest of the globe to follow.

With technology that is now being actively designed toward their needs and uses, the elderly enjoy compounding beneficial effects of the digital revolution: they are better able to access, afford, and exploit technologies and the secondary products and services they support. Governments also follow suit; over half of their voting-age constituents are 65+, and services for them can now be easily used to support specific government services.

As producers, Pittsburgh’s elderly are also further empowered. Their quality of life is both better preserved and better supported by the latest technology, empowering them to contribute more quality and quantity to the workplace than previously possible. Within the workplace, this further compounds corporations’ cognitive diversity to include a stage of life not previously represented, giving further voice and visibility to their experience.

Changes in the workplace also cause a shift in the balance of wealth within families, in turn negating the need for younger family members to move away for economic opportunities. With the ability to keep the nuclear and extended family together physically, individuals and families can maintain their ties to place, community, and one another. This allowance is the lynchpin for further positive feedback loops at the individual and community level.

At the neighborhood and community level, individuals and institutions are now incentivized to invest in place and each other long-term. Downstream implications on ecosystem and sustainability still years away are considered critical to present decision-making, because the stakeholders are constant, and have seen cycles of change come and go. Social bonds strengthen over time, and the pace of life slows down long enough for neighbors to reach depths inaccessible in previous touch-and-go culture.

Finally, at the individual level, the biggest contributing factors to the social isolation of Pittsburgh’s elderly have been largely mitigated, if not entirely reversed. Just as groups and institutions are incentivized to invest long-term, so are individuals as they age; they are no longer forced to choose between abandoning their friends and community to be with family, or giving up those they love to stay close to the life they’ve built. Their own needs and abilities couple with those of their family; no longer a burden, they contribute in both income and safety/stability/security. And as they do inevitably age, their need for love, care, and attention couples with those of later generations, from their neighbors and local care workers to their very own grandchildren. “Social isolation” is no longer an inevitability, it is an occasional anomaly with safeguards in place to keep it relatively minimal and benign.

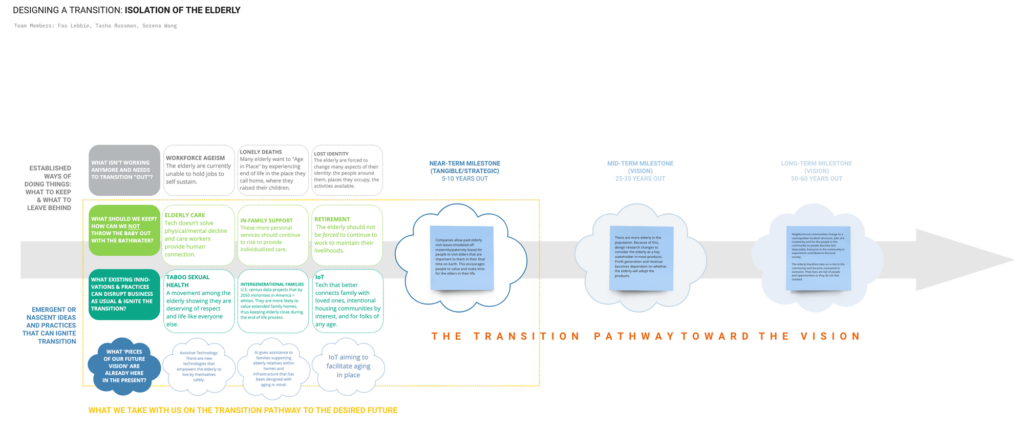

4.2 Backcast and Assessing the Present

Having already forced ourselves to consider the future in a vacuum, the second phase of our work was to backcast from that future and to assess the present, in service of building milestones that would serve as the skull, spine, and pelvis of the skeleton of our future transition plan to a desired future. Note: these milestones are not permanent; rather, they are a mechanism for our team to transition ourselves from just thinking about the future, to starting to consider how we might get there, and what we’d like to take/leave from the present as we do so.

Mapping

We based our mapping primarily on a matrix developed to chart established/existing practices and ways of doing things, and new and emergent ones. We did this through two exercises, completed in the following order: (1) Taking Stock, (2) Envisioning the Long-Term Transition.

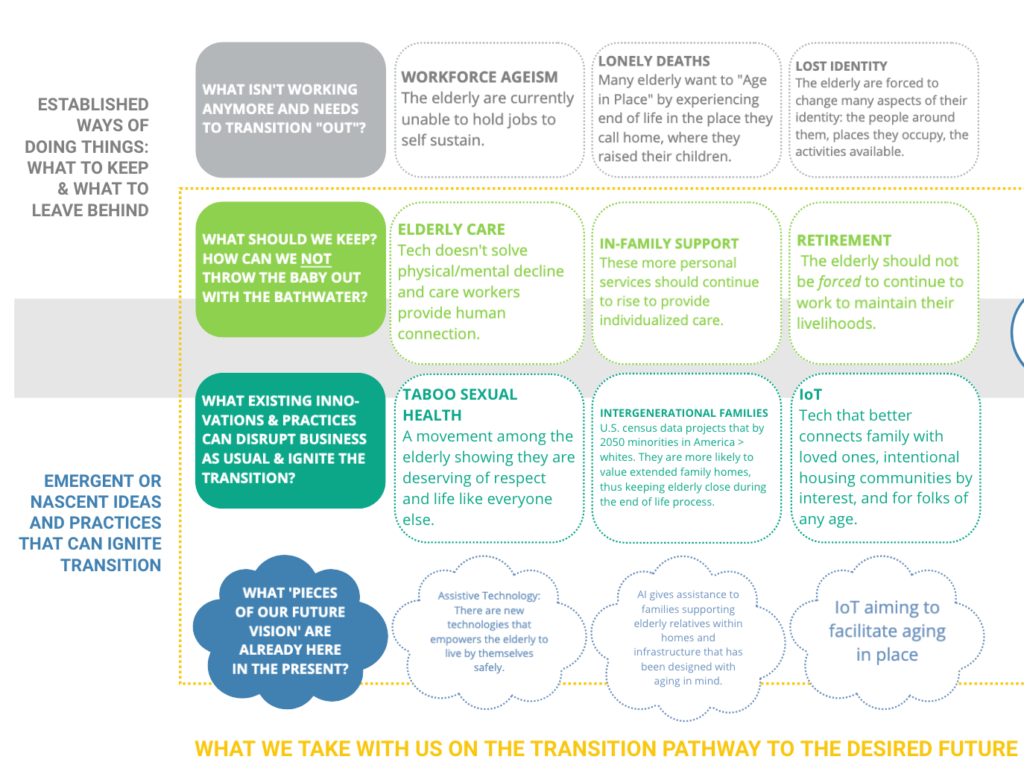

Exercise 1: Taking Stock

As seen below, this first exercise breaks the overall transition down into a few more manageable initial questions that separate the wheat (what elements do we want to keep and/or include as we transition*?)* from the proverbial chaff *(*what elements from the present do we want to exclude?).

As we had done in the previous section, our team divided the work across members so that each of us would contribute a variety of content across each theme.

What isn’t working anymore and needs to transition “out”?

The team highlighted several ideas we’ve seen pop up time and again throughout this assignment: workforce discrimination as a root of financial and cultural dependency, lack of opportunity to age in place, and the corresponding tumult in identity and everyday life that transitioning to old age entails. In retrospect, even these three ideas can be attributed to one another in a greater narrative characterized by the positive counterparts to these ideas: one in which access and support to meaningful work opens doors to a more meaningful and stable sense of self, family, and community.

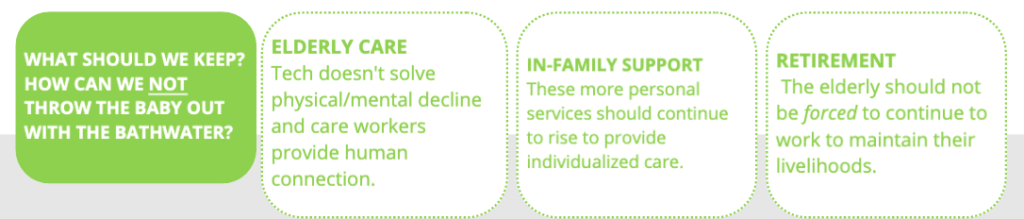

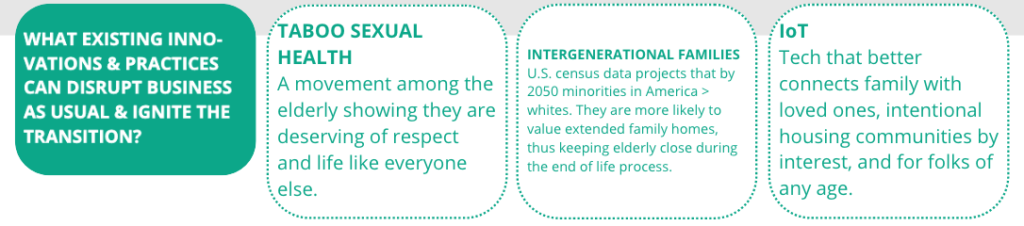

What should we keep? How can we avoid throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

Here we see a variety of ideas that all play into the theme of care work discussed in previous sections. Aspects of current life that we think are important to maintain in the future are care workers to support the inevitable needs that come about with aging, in-family support services, and the spirit of government and corporations contributing to eldercare through pensions and social support. Here we see a direct link to the first phase of our work, Developing the Future, in which care work appears critical across layers at the family level, the neighborhood/community level, and the regional/governmental level.

What existing innovations & practices can disrupt business as usual & ignite the transition?

For the first time, we see significant variety in the responses provided by various team members. Themes spanned cultural innovation (the sexual health movement as an indicator of respect and vivacity), demographic changes (BIPOC elders driving momentum to age in place), and technological innovations (technologically- and socially-based support for community and sense of belonging). After focusing so extensively on the many complexities surrounding present-day problems, our team found it refreshing to begin to frame shift to seeds of life that have already been planted around us. This is distinct from the previous exercise because we were formerly futuring in an entirely fictional world; it was a breath of fresh air to see that there are, in fact, a few building blocks already in place.

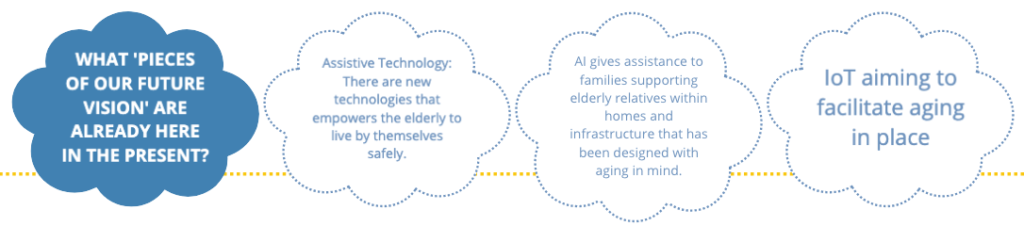

What pieces of our future vision are already here in the present?

Continuing the metaphor of seeds already planted, our team cited several pieces we already see in the world around us: the tech industry publicly setting concerted goals and metrics to support aging generations, breakthroughs and research in assistive technology that have already been made, and AI-supported infrastructure at scale. It’s interesting to note the homogeneity of the team’s responses to this final question, especially in light of the variety we saw in the last one. This could be attributed to personal experience (we are, after all, studying at a technological university) or it could be indicative of the greater present climate in which most of society turns to technology for innovation and/or solutions, often overlooking less sexy and/or less scalable solutions.

This juxtaposition is also intriguing as a potential bridge; much of what we’ve highlighted as positive pieces of the puzzle focus on distinctly human aspects of life: belongingness, family, care work, etc. Thus, one aspect to further investigate in later work is the extent to which technological innovation could, in fact, facilitate points of intervention that open the door to these human experiences while recognizing its role as a facilitator, as opposed to a replacement.

Exercise 2: Envisioning the Long-term Transition

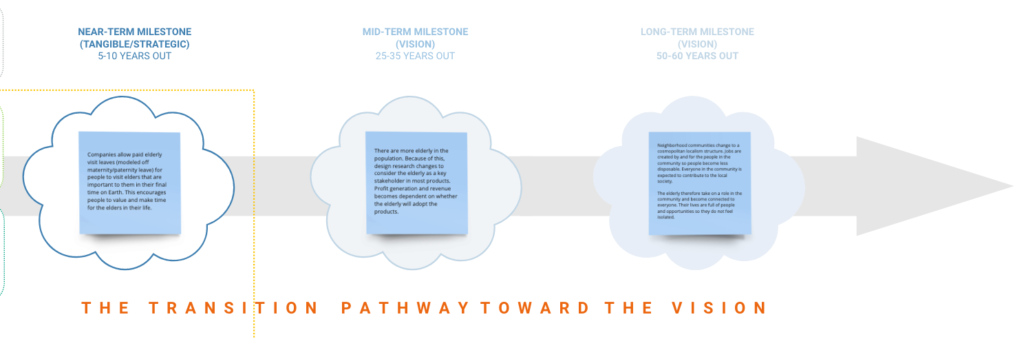

Once Exercise 1 was completed, we re-grouped to adjudicate and synthesize our responses to be able to map them into milestones set in the short- (5-10 yr), medium- (25-35 yr), and long-term (50-60 yr) range. We framed our milestone as “moments in time;” further detail on each is provided below.

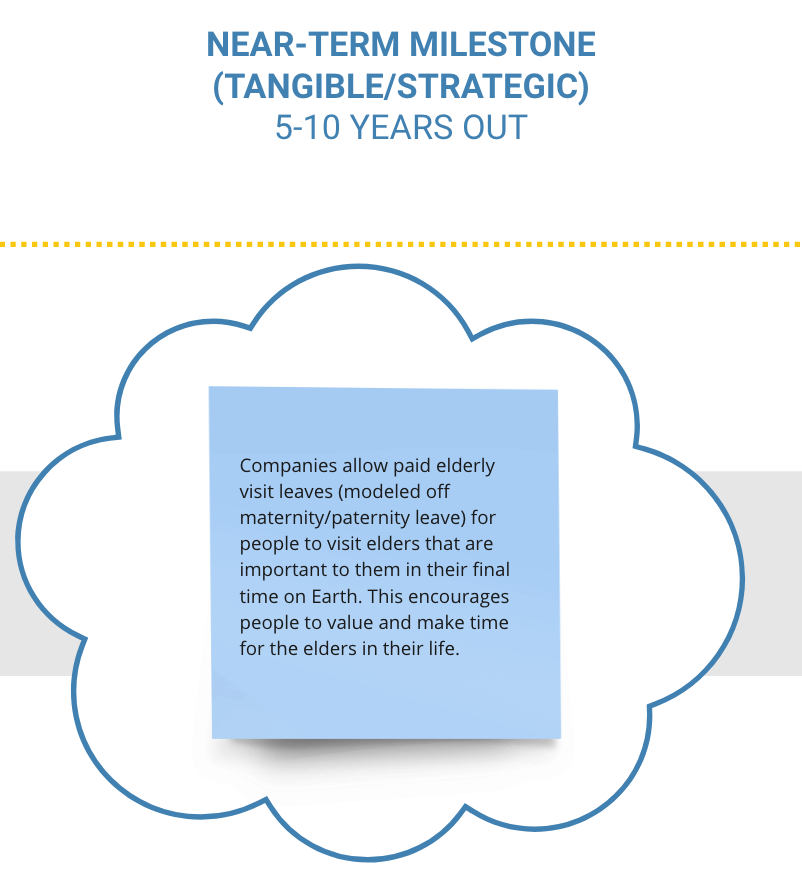

Short term: 5-10 years out

Our first milestone was the near-term: 5-10 years out. This milestone aimed to capture the most desirable tangible objectives we had outlined while “taking stock.” We agreed on a maternity and paternity leave system for the care of elderly relatives whereby individuals who needed time to care for their relatives could get paid time off, reducing the burden of providing such support. We thought that this change would make people visit and therefore value the elderly more.

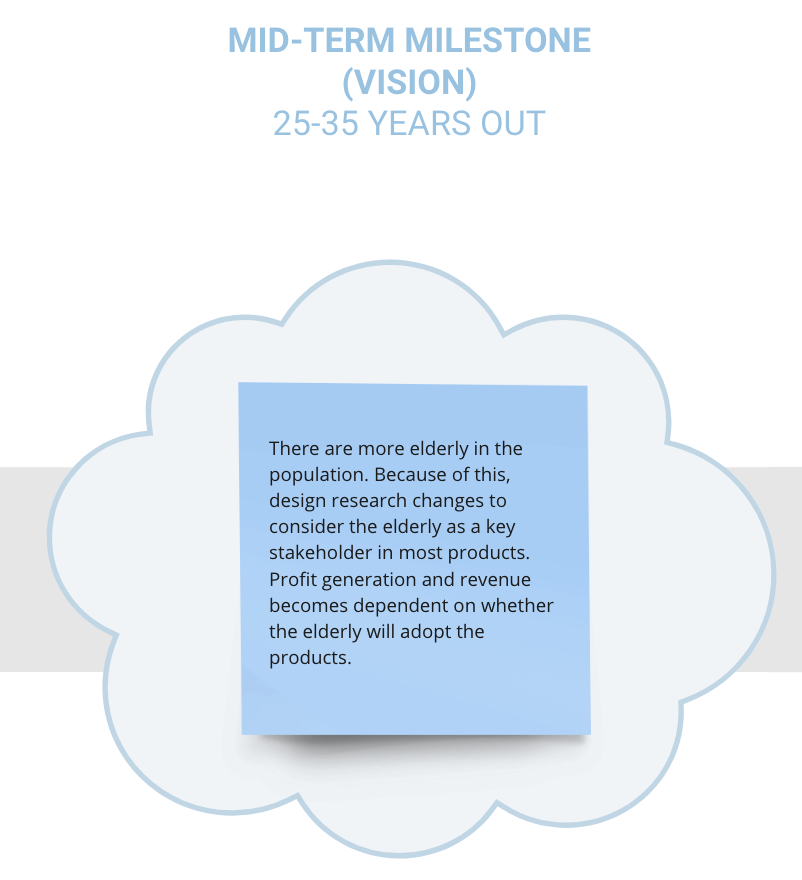

Medium term: 25-35 years out

Our mid-term milestone covered events 25-35 years out. After this amount of time, the aging population would have a significant impact on the demographic make-up of Pittsburgh, and therefore businesses and the government would be forced to more carefully consider how their policies and products would be received by the elderly. We envisioned this development making life substantially easier for older people.

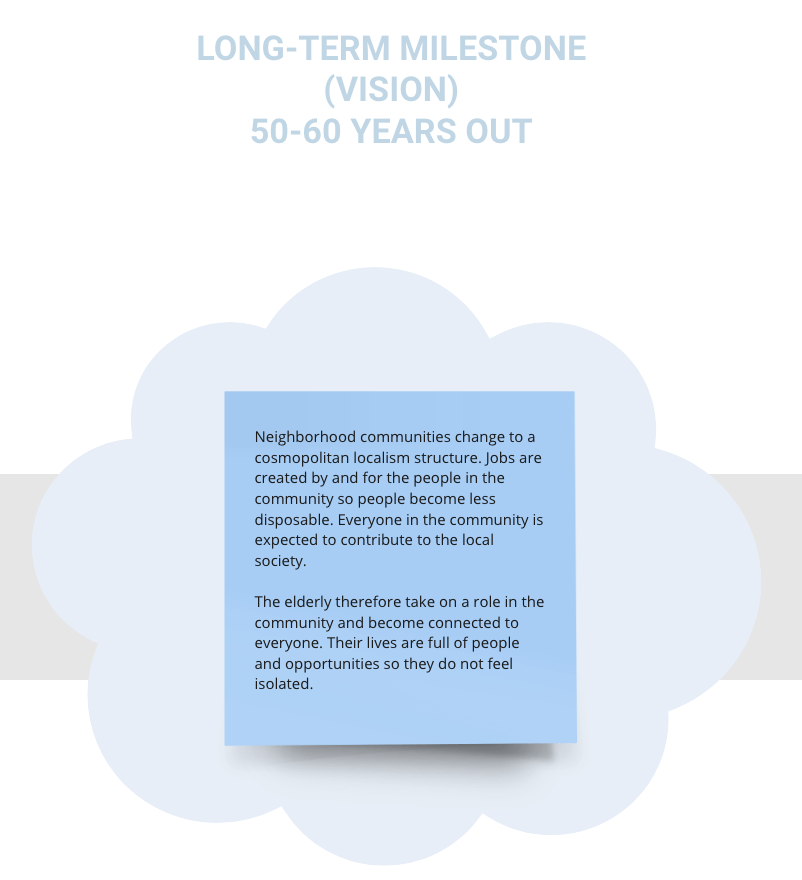

Long term: 50-60 years out

Our long-term milestone looked 50-60 years into the future. We envisioned an optimistic future whereby the elderly become functional community members. Cosmopolitan Localism could be leveraged to create opportunities for the elderly within their communities, and they can remain in proximity to their home.

Once we had created the milestones, we each made sure to refer back to the taking stock stage to ensure everything we had stated fell within the milestones. On observing “taking stock,” we concluded that we had been successful and needed only to conduct minor tweaks to ensure a consistent narrative.

Reflection and Next Steps

While mapping our desired future for experiences of older citizens of Pittsburgh, what we uncovered was more inevitability than speculation because most of our observations emerged from considerations of the impact of changing demographics. By 2060, around 150 million Americans will be over 65, accounting for as much as half of the total U.S population. The impact of their consumer and political decisions will become far heavier than it currently is, and therefore government and business must begin to consider how they will account for this new base. Team Resilience speculated upon seismic changes to all families’ cultural and social fabric, the way we care for the elderly, and what value older Americans can add to society. These perspectives of an envisioned future that has dealt with the wicked problem of isolation amongst the elderly may form crucial steps in the right direction for tomorrow’s businesses, government, and community.

Our visions of the future will also form crucial pathways to our creation of Assignment 5 which requires us to translate them into tangible interventions. It will be fascinating to see what ideas we can come up with that are leverageable in moving towards our desired transition.

Assignment 5: Designing an Ecology of Interventions

Collaborators: Fas Lebbie | Tasha Russman | Serena Wang

Introduction

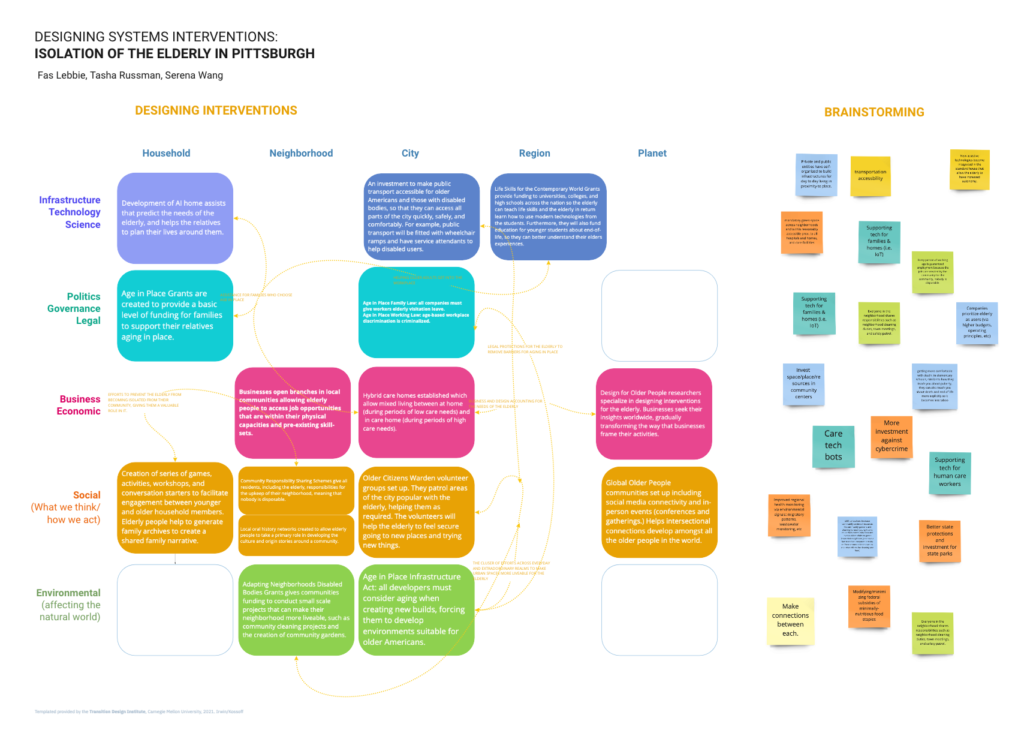

The goal of our fifth, and final, phase of our work around Social Isolation of the Elderly in Pittsburgh was to develop an ‘ecology’ of systems interventions that together lay the foundation for moving the needle on the issue, so to speak. Before diving into the what and how, it’s important to first understand the why. The nature of this, and many other wicked problems, is complex, multifaceted, and situated within layers of relationships and histories. With this in mind, it’s important to understand the many factors at hand within the present, and with an eye toward the future; after all, there is no better time to begin something than the present. Our interventions map was put together with today’s realities in mind: constraints that range from budgets to timelines to geographic/strategic/thematic areas of interest. Our own goal is to represent interventions in both a digestible and situated way, so that any one individual or institution can see both how a single change can make a difference on its own, and/or in collaboration with others. Let’s now dive in.

Process

This final step culminates months of research across several lenses and bounds; reflecting this, we used a matrix that crosses variables we’ve seen in previous phases: one axis charts levels of intervention (from Household to Planet), and the other differentiates type (i.e. Infrastructure/Tech/Science, Politics/Legal/Governance, etc). As a team, our process covered several broad steps, through which we moved from divergent ideas to a final narrative.

First, we took a look at our own work from across the project to prime ourselves on the topics, themes, and conversations that underlie our investigation as a whole. It should be noted that we viewed this final step in our process as one better described by the term curation than design. Indeed, the ingredients had all been laid out before us in the form of our prior work – the question of intervention was less about what and more about the form they would take. For example, there were several themes that came up over and over again throughout our research: ability to age in place, legal protections in the social square and marketplace, and access to transportation, just to name a few. Previous work had also surfaced more grounded ideas such as a workplace benefit for eldercare, modeled after the current parental leave model. In this way, a quick look at our older work armed us with both ingredients and entirely designed solutions already at our fingertips.

Each of us then brainstormed our ideas separately in an attempt to cast a wide net free of the dynamics of groupthink, before then coming back together to bring our many ideas back together on a first draft of the matrix. Unsurprisingly, we found several ideas that overlapped between all of us, a few complete outliers, and several more that lay somewhere in between. Again we found that earlier key research themes proved integral among all our ideas, resurfacing basic ideas such as more livable and green community spaces for physical, social, and mental health of elders and their surrounding communities. We took several days’ break before our next session together to dis-engage again from the material, and promote more creative thought as a result.

Our following session saw us adjudicate and massage at both an idea- and thematic-level. We explored ideas that were half-baked, adding to them where possible, and throwing them out where they didn’t hold water. Likewise, we looked to emergent themes, and expanded them further where possible. A benefit to the visual nature of the matrix we used was that it highlighted vacant spots as immediately apparent; we pushed ourselves to ideate further in these areas, building on themes that had already begun to tie together the rest of the ecology before us. This step was a key one because it forced us to consider areas not as readily accessible in our brainstorm; for example, planetary-level interventions for elders proved more difficult than more localized, neighborhood-level ones. It was important to us that we not discount ideas simply because of a failure of imagination. Likewise, this forced us to recall more areas we had all also overlooked in our review, such as the basic idea of accessible transportation services and other critical infrastructures.

Finally, we again honed our latest iteration of the ecology; we connected the final ties of the ecology, and cut the loose threads where ideas didn’t support one another in the greater scope of the ecology. In truth, and perhaps unsurprisingly, many of those “loose threads” were those same ideas that had been added in the most recent step, as was the case with most planet-level interventions. On the one hand, this may very well represent the bias of our research team and/or the subjective nature of ideation. On the other hand, we believe that both the extra push, and the final trim were both important steps in our process in an effort to build, affirm, and reaffirm the efficacy and collaborative nature of the ecosystem we built. Additionally, this final step reiterated a standing hypothesis that we had carried around the import of locally-based solutions regarding both our own wicked problem, and its overlap with many related issues. Until this final step we had held that “the more local the better” as an assumption; only after adding, and then re-trimming, ill-fitting solutions could we come back to that assumption with a higher level of conviction around its import in the greater scope of the tapestry of solutions.

Content

Our matrix covers several prominent themes, nearly all of which are highly synergistic both between and within each other. Given the constraints of this write up, we will focus on three key themes as a basis for exploring the majority of the matrix: 1) Interventions that make local spaces more livable, 2) Assistance for families who stay in place, and 3) Helping older adults in the workplace.

1) Interventions that make local spaces more livable

We’ll start with interventions that make local spaces more livable because in many ways they represent the “yin” to the “yang” in social isolation: for the ways in which social isolation is immaterial (i.e. mentally/socially/culturally-driven), we find that physical interventions can play a huge role in “getting unstuck” from the issue. Likewise, for the facets that are material (i.e. physical/educational/technological access to critical infrastructure), the interventions that are most needed are cultural and social ones. Let’s take a look at two interventions that, together, exemplify the richness of this area.